They had a record six teams in the tournament but one by one they tumbled out, failing to live up to expectations, dashing the hopes of an entire continent.

The vuvezelas may still be screeching and organisers saying all the right things about the show going on but no-one can ignore the hugely disappointing performances of Africa’s teams at Africa’s World Cup.

A string of first round flops by African teams on home turf could not made a greater mockery of Pele’s famous comment that an African team would win the World Cup early in the millennium.

Barring an unlikely goal avalanche from the Ivory Coast, only Ghana will fly the flag for Africa going into the second round. So what now? Having given Africa an extra place in this World Cup, FIFA will be under increasing pressure to redress the balance in Brazil in four years’ time and take one away.

FIFA President Sepp Blatter may be at pains to promote the sport in less successful continents but South American countries have long cried foul, given their success rate, about sharing parity with Africa when it comes to the number of places allotted in the finals.

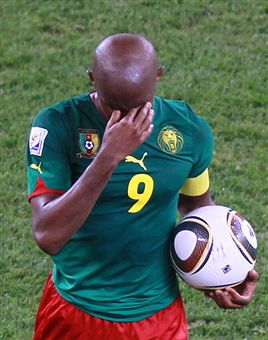

Many believe Arican teams have only themselves to blame for the failure to silence their critics once and for all. Take Cameroon. Questions are being asked of coach Paul Le Guen’s selections amid reports of massive splits in the camp with senior players incredulous at younger inexperienced teammates being drafted in at the last minute to carry out a far too difficult task.

“They couldn’t withstand the sort of pressure that comes with playing in big tournaments,” said midfielder Achille Emana as his team flew home.

For all the tactical organisation coach Lars Lagerback brought to the Nigerian side and the team spirit he has supposedly fostered, the Super Eagles suffered from a distinct lack of cutting edge and creativity.

The “Group of Death” may have been unkind to the Ivory Coast but for all Sven Goran Eriksson’s assertions about this being the happiest squad he has ever worked with, three weeks is a pitifully short period to create momentum.

Overrated and overpaid was how one South African newspaper described Carlos Alberto Parreira, coach of the first host nation to be eliminated at the group stage, who ended up paying for the decision to leave Benni McCarthy out of Bafana Bafana and play others out of position.

Cameroon icon Roger Milla, whose legendary corner flag dance routines became a hallmark of the 1990 World Cup, says the problems for African sides were deep-rooted. “There has been a lack of discipline and organisation among the African nations,” says Milla now 58. “I knew, for instance, that Cameroon would have problems. The coach simply didn’t do his job properly. He simply didn’t pick the right players. If you are a serious manager, you should be more rigorous and not be dictated to by the players.”

Cameroon icon Roger Milla, whose legendary corner flag dance routines became a hallmark of the 1990 World Cup, says the problems for African sides were deep-rooted. “There has been a lack of discipline and organisation among the African nations,” says Milla now 58. “I knew, for instance, that Cameroon would have problems. The coach simply didn’t do his job properly. He simply didn’t pick the right players. If you are a serious manager, you should be more rigorous and not be dictated to by the players.”

Milla denies African sides got ahead of themselves by thinking they could just turn up but says there has been too much interference by self-interested parties. “There are mistakes that need to be corrected, like not having a whole federation making decisions,” says Milla. “You can’t have 90 people making decisions on 23 players.”

Bora Milutonivic, who has taken no fewer than five countries to the World Cup finals, is another who believes a change of attitude is needed.

“At club level everything is controlled for the players,” he says. “They don’t have to think, they are in a disciplined system. But then, when they come back home, they cannot adapt and take responsibility properly for themselves.”

Bora, who took Costa Rica in 1990 and Nigeria in 1998 to the second round, as well as Mexico in 1986 and the United States in 1994, albeit when both were hosts, says getting inside players’ heads is paramount when European coaches are employed by African nations.

“The first thing I did was get to know my players. If I have a player from Ajax then I know for sure that, yes, he can play; he does understand. But the others I have to know where they come from - I visit their family, their home, where they grew up, know their culture and their religion.

“Also, you need more than a few days or weeks; you need several months. It’s not only going to watch your players with European clubs. You have to know where they come from, to know who they are.”

Milla agrees. ”Every team has its way of doing things and that’s what I’m concerned about. Maybe foreign coaches need to understand the country better. And not just come in at the last minute.”

Andrew Warshaw is a former sports editor of The European, the newspaper that broke the Bosman story in the 1990s, the most significant issue to shape professional football as we know it today. Before that, he worked for the Associated Press for 13 years in Geneva and London. He is now the chief football reporter for insideworldfootball