Manchester United’s match with Rangers in the Champions League was more than a mere group match where the Scottish manager of the English team, Sir Alex Ferguson, was playing the side that had scorned him in his youth in Glasgow.

It was all our footballing pasts rolled together and it illustrated why Scottish football is at such a low ebb and may go even lower before it recovers, if it ever does.

It is also a salutary lesson on how the balance of power between Scottish and English clubs has changed. So much so that the Scots, who once led the English, are now a very poor relation, as Rangers’ manager, Walter Smith, all too readily, acknowledged.

Now, before anyone jumps to the conclusion that I start with an inherent prejudice against the Scots, let me say that, as a child of the 60s, I was brought up on the great Scottish names that lit up the English game: Dave Mackay, Alan Gilzean, Denis Law, Billy Bremner, Peter Lorimer, Eddie Gray, and then, in the 70s, Kenny Dalglish, Graeme Souness, Alan Hansen, Charlie Cooke, Steve Archibald and many, many others.

If I did not quite believe that north of the border was the land of footballing supermen, as Alex Ferguson once said in jest, I always believed that Scottish football had flair, a touch of magic and that a Scot with a ball could do things that an Englishman just could not.

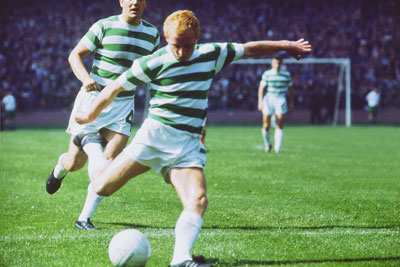

I only had to see Jimmy Johnstone (pictured) tormenting the English backline to be reinforced in my view. And I experienced much joy at Celtic becoming the first British team to win the then European Cup. The Scottish national team was often a disappointment but there was something about Scottish football that promised class and often delivered the unexpected.

I only had to see Jimmy Johnstone (pictured) tormenting the English backline to be reinforced in my view. And I experienced much joy at Celtic becoming the first British team to win the then European Cup. The Scottish national team was often a disappointment but there was something about Scottish football that promised class and often delivered the unexpected.

This was carried into the financial and social sphere in the 80s when David Murray took charge of Rangers.

It is easy to forget now that he has stepped down and Rangers are in financial trouble. What an innovator he was, both on and off the field. On the field, by hiring Graeme Souness, he did much to break the sectarian barriers between Protestants and Catholics that had so marred football north of the border.

Off the field, his efforts to modernise Ibrox and generate resources by using the club, not merely as a place for football, but also for marketing products was an innovation in the British market. I remember going up to my first Old Firm Derby in the late 80s and being struck by the new stands at Ibrox. Also striking were the range of products, such as whisky and others bearing the Rangers’ label, being sold to the fans. The Murray idea was that, if fans liked a drink and they were Rangers supporters, they would rather drink the Rangers’ brand of whisky than any other.

English clubs closely studied what Murray (pictured) had done, in particular his bond scheme where fans were encouraged to buy season tickets for several years in advance.

Murray had used the scheme to finance the Ibrox redevelopment and this idea found an instant convert in David Dein, then vice chairman of Arsenal.

This was years before Arsenal had any thoughts of moving from Highbury. Dein was very keen to make the stadium all-seater and the Bond scheme seemed ideal for financing it. West Ham, too, was much taken by the Murray plan and launched their own bond scheme.

Murray did not just provide blueprints, he actually helped implement the plans, having his own finance company which provided advice and guidance on the bond scheme. Not all the Rangers’ promise was fulfilled. The Arsenal bond scheme was not a triumph although it worked well in part. The West Ham one was an abject failure not helped by West Ham getting relegated. Murray emerged on the scene as English clubs were reeling from Heysel, which had led to the ban from Europe, and then Hillsborough. They looked north in admiration and hope that the Scots could come up with the ideas to rescue English football.

So what went wrong? Two things.

In 1992, UEFA, trying to rescue a moribund European Cup, launched the Champions League. The same year, the top clubs in England persuaded the FA that it would be in the national interest for them to break away and form the Premier League. The economic consequences of this were to prove so game changing that, suddenly Scotland, the innovator, became Scotland, the mendicant, asking for favours from England.

Nothing illustrates this better than how the fortunes of Rangers and West Ham changed. When West Ham took advice from Rangers on how to raise money to upgrade Upton Park, it was a much smaller club than the Scottish giant. By the time the Premier League had been going a few years, West Ham was earning more and did not need Scottish guidance.

All this has not been helped by a lamentable lack of leadership and any strategic vision from the hierarchy of Scottish football.

As income has gone south, it has chosen to wear the hair shirt of victimhood and tried to hold on to what it has had without seeking to profit from change. This is best illustrated in its ostrich like attitude to refuse to accept that a British football team is both necessary and inevitable in the 2012 Olympics.

Speak to the people at the English FA and they cannot work out why the Scots remain so opposed. Listen to Trevor Brooking, the FA’s Director of Youth Development.

As he put it to me recently, “I’d like to think we are going to get an England team at the London Olympics but it is a sensitive thing. Yes, the Scots are still opposed to it but nobody wants to bring it out into the open too much till the December decision on 2018. I think, once that’s decided, then there would have to be a decision. We would definitely have a team, whatever it is. Whether it will be all English or the other home nations will take part will not be decided till after the result of the bid is known because it has became a bit of a conflict.”

Here was Scotland’s chance to accept the inevitable but try and profit from it. It has had repeated assurances that it will not affect Scotland’s position in UEFA and FIFA. But the Scots refuse to believe these assurances.

They would have been much better advised to take part in a British team in 2012 but use it to get concessions from its powerful southern neighbour, concessions which could help revive its football. But the Scots cannot see that. No surprise then that Rangers, once the giants of British football, is now a team that probably lags behind Blackpool, let alone West Ham.

Mihir Bose is one of the world’s most astute observers on politics in sport and, particularly, football. He formerly wrote for The Sunday Times and The Daily Telegraph and until recently was the BBC’s head sports editor.

.jpg)