Funny game football, they say, Except that no one is laughing at the moment.

What with the sexist piggery at Sky, the sordid squabbling over who kicks off at the Olympic Stadium after 2012, the ineptitude of those who run the game, the ever-escalating greed-is-good philosophy of the Premier League and those who play in it, you would think it would be a total turn-off by now.

But perversely, the public continue to turn on.

I have long felt that the game I covered for many years no longer has a soul. It is not that it has lost it. Rather, sold it.

Sport is not just about football, though most football people will tell you that it is. What happens to the Olympic Stadium is an opportunity to show it should not be.

But breath should not be held in the battle between West Ham and Tottenham, though Barry Hearn’s Orient may have queered the pitch, so to speak.

What really has brought home to me the fear that morally football may now be beyond redemption is the fact that when Southampton play Manchester United in the FA Cup this Saturday evening the one man who, more than anyone, deserves to be there in a place of honour will be absent.

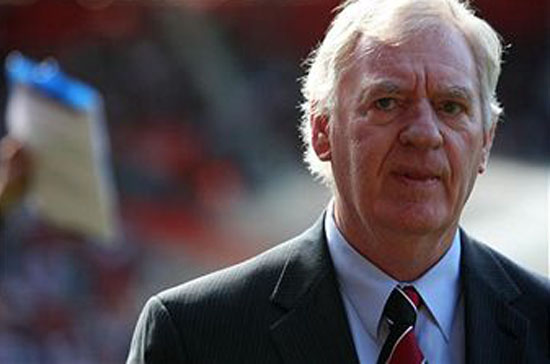

Thirty-five years ago Lawrie McMenemy helped create the most memorable day in Southampton’s history when he led them to that momentous FA Cup final triumph over United at Wembley. Alas, he won’t be at St Mary’s Stadium to see if this victory can be repeated because he hasn’t got a ticket.

This despite his long association with the club as a former manager, director and consultant. When the new regime, headed by the late Swiss industrialist Markus Liebherr, took control 18 months ago McMenemy was told there was no longer a regular place for him as a guest in the directors’ box, though he was still welcome as a paying fan, but without his usual place in the car park.

Not only that. The photograph of Southampton’s finest hour-and-a-half, with McMenemy holding aloft the FA Cup – their only major trophy – has been removed from the boardroom. In its place now is a montage of the club’s victory last season in the mighty Johnstone’s Paint Trophy.

McMenemy was told by chairman Nicola Cortese –labelled “draconian” and a “control freak” by the local paper after banning photographers from the ground so the club could sell their own photographs to media outlets – “You have to accept that the game has moved on.”

He says he acknowledges this but rightly asks: “Does it mean you must totally ignore what has gone on before?”

McMenemy still watches as many League One matches as he can, parking his car in a nearby garage, walking to the stadium and getting to his seat through a side entrance, as apparently he is no longer considered VIP enough to enter through the foyer.

Sad, isn’t it, And how un-Saintly.

But Lawrie McMenemy MBE is a big man with big memories. And if football has moved on, then so has he.

Big Mac, now 74, one-time assistant manager of England and manager of Northern Ireland, who signed and nurtured some of the biggest names in football – Kevin Keegan, Alan Shearer, Alan Ball and Mick Channon among them – these days has his own special mission in life.

As a football manager his career embraced moments of humiliation, like getting the sack at Doncaster, and of elation, like that FA Cup win over United.

But, he says, nothing is etched more in his mind than the week he spent in Dublin eight years ago watching thousands of young people taking part in a sports event that was special in every sense.

This was the Special Olympics, designed to give those who have learning disabilities the opportunity to express themselves lucidly and bravely through sport.

“When I got the call to become associated with the Special Olympics, like most people I assumed it was Paralympics, but when I went to their World Games in Dublin it was a real eye-opener,” he told me.

“It really hit me what it was all about. I’ve always been one for the community. When I was in football I always believed that the game and the clubs should be an integral part of the community.

“It’s not a question of being a do-gooder. If someone thinks it will help their cause by sticking my name on it, who am I to say no?

“In Dublin there were 80,000 people at Croke Park. The USA team’s ambassador was Muhammad Ali, riding in a golf buggy. U2 were top of the bill with Riverdance at the opening ceremony and then Bono came on with Nelson Mandela.

“It was televised all around the world, except in Britain of course. I mean you can’t interfere with Ant and Dec, can you? There were 8,000 athletes from 160 countries, and I am sat there going, whoa, what is this all about?”

Two years later McMenemy took over as chair of the Special Olympics of Great Britain. He has since become President.

“I know that when you are dealing with the disabled, whether it is Down’s Syndrome, autistic or whatever, some people are not comfortable with them, but I found that having to live with the big names and the big stars made it easy because you treat people all the same.

“You have to win their trust and laugh with them because, as Jimmy Savile said to me once: ‘If you don’t have a laugh, you’ll have a cry’.”

In the summer of 2009 McMenemy presided over the Special Olympics GB Summer Games, the biggest multi-sports team event to be held in the UK before 2012. Some 2,700 competitors took part in 21 sports in venues spread around the city.

“There are 1.2 million people in this country with learning disabilities, so it is good that they can be recognised through sport in this way,” he said.

According to the World Health Organisation, up to three per cent of the world’s population has an intellectual disability – that equates to 200 million people, representing the largest disability population in the world.

On Monday week football gets a welcome opportunity to show itself in a better light than of late when the Premier League hosts the Special Olympics’ first-ever Football Development Strategy.

McMenemy will be there to explain how football clubs and organisations can support the growth of the sport among people with learning disabilities.

While he would not profess to be a Saint himself, McMenemy, of course, was one for much of his football life, which is why he has been saddened at the decline of Southampton.

“You would never have dreamed a club like Southampton nearly went out of business. The problem was, when it became a plc it stopped being run the way it had been for a hundred years by people in the community who ran it for the supporters.

“I like to think that by winning the FA Cup, being second in the league and in the League Cup final, and having a little tickle at Europe, I did my best for a happy, professional outfit. But the way it started to be managed financially [Southampton went into administration and were docked ten points] took it to the knife-edge.

“You are talking about a club which had two managers in 30 years – Ted Bates and myself – to one which had nine managers in three years and three in one season.”

When the man who managed the club for 12 years, returned as their director of football and has the Freedom of Southampton, was told that from then on he would have to pay and watch from the terraces, it was no wonder he felt rather hurt. Parsimony is one thing; pettiness another.

Although he will only be watching on TV, McMenemy wishes the team luck against United. “Anything is possible. We proved it at Wembley all those years ago. But more than anything I want to see us back in the Premier League.”

As a vice-president of the League Managers’ Association McMenemy has been trying to get cup medals awarded retrospectively to managers and coaches.

He tells how, in a League Cup final, he was tugged up to the Royal Box by opposing manager Brian Clough.

“Come on, young man,” he said, “we are going to get something out of this.”

I think it was the President of UEFA who was awarding the medals. He looked perplexed but they scrabbled around and gave us a box each. When we looked in them later, they were empty.

“I’ve got a grandson who idolises me, but one of my biggest disappointments is that despite all my years in football and all I’ve done, I haven’t got a medal to show him.”

At least in his new role McMenemy has been handing out medals to other people’s children and grandchildren who have been striving to overcome their personal handicaps through sport.

And that, for him, makes it rather special.

Alan Hubbard is an award-winning sports columnist for The Independent on Sunday, and a former sports editor of The Observer. He has covered a total of 16 Summer and Winter Olympics, 10 Commonwealth Games, several football World Cups and world title fights from Atlanta to Zaire.

.jpg)