FIFA is facing its own News International moment with its corruption scandal. News International thought that by saying phone hacking was the work of one rogue reporter, Clive Goodman, the royal correspondent, and his confidant Glenn Mulcaire, it could isolate the problem. As the world now knows, it could not.

FIFA is in danger of making a similar mistake if it thinks the corruption scandal has been dealt with once the Ethics Committee finishes its work on July 23. Let us consider what is in store for this day.

On that day, we shall know the fate of Mohammed Bin Hammam for his alleged attempt, in May, to bribe members of the Caribbean Football Union in Trinidad during his aborted FIFA presidential campaign. It is alleged that bribes of $40,000 (£24,000) were paid or offered to each member. Caribbean Football Union officials Debbie Minguell and Jason Sylvester, who were suspended along with then FIFA vice-president, Jack Warner, will also hear their fate.

If the leaks that have emerged from the Ethics Committee are any guide, the case against the accused, particularly the Qatari, looks a formidable one. All three must, for now, be considered innocent. They may, or may not, be found guilty, and they may, or may not, appeal against an adverse decision. However, all the signs are that FIFA will present the report to the world, and then claim it has investigated the only piece of hard evidence it had on corruption. So as far as FIFA is concerned, it will have done its job and the work will now be over.

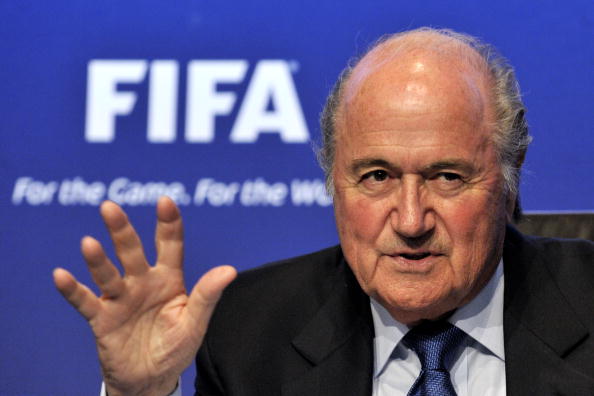

FIFA will be gravely mistaken if it takes that view. The world outside will not think that. If FIFA believes that what the world thinks does not matter, all that matters is the FIFA family, to use Sepp Blatter’s favourite phrase, then it would do well to study what has happened to News International. That fostered the idea that what mattered was the Murdoch family and that attitude has resulted in the very future of the family, certainly as a media player in the UK, coming under scrutiny.

The problem for FIFA is that, like the Murdoch empire, it has lost credibility and it cannot regain it with one Ethics Committee report. It needs to go much wider and, above all, it needs to show humility and acknowledge that it is not as powerful and mighty as it sometimes pretends to be. Hubris, as the Murdoch story shows, comes before a fall and FIFA has also been guilty of that.

So consider how FIFA treated Warner and how the world has reacted to that. It is now abundantly clear that Warner’s decision to resign followed immediately after he had seen the Ethics Committee report. This could not have been more damning as it concluded he had “knowledge of the respective payments and condoned them. It seems quite likely that the accused [Warner] contributed himself to the relevant actions, thereby acting as an accessory to corruption”.

FIFA then put out a statement regretting his departure, lavishly praising him and declaring that “as a consequence of Mr Warner’s self-determined resignation, all Ethics Committee procedures against him have been closed and the presumption of innocence is maintained”. But if FIFA thought this closed the long and often controversial football career of Jack Warner, consider how the House of Commons Select Committee on Culture, Media and Sport reacted to this. Its report was scathing of how FIFA had handled the 2018 World Cup bids. And when I spoke to John Whittingdale, the chairman, he drew particular attention to the Warner episode.

Barely able to conceal his astonishment he said, “The Ethics Committee report we understand has serious questions to answer on the part of Jack Warner. He then resigns and FIFA says we don’t need to do anything and will drop the investigation. That is extraordinary.”

Now, FIFA stalwarts will argue, as they have, that once Warner resigned there was nothing they could do. FIFA is not a government organisation. It is, at the end of the day, a voluntary body. Even a national football association does not have to belong to FIFA. As we know, for several decades the British home nations chose to stay out. There are many who suggest they should now do the same again if FIFA cannot be reformed. FIFA has no police powers and no powers to summon non-members or those who are no longer members. As FIFA has itself discovered when dealing with unregistered football agents, it cannot touch them as they are not subject to FIFA’s rules. All FIFA can do is impose sanctions on clubs and players who deal with such agents.

Interestingly, Whittingdale’s committee also has limited powers. It can only summon British citizens, and it is worth nothing that during its investigation into the 2018 bid, neither David Dein, who played such a prominent part in the English bid, or Andy Anson, the chief executive of the bid, gave evidence. Dein said he could not come the day the committee had asked him to, but Whittingdale admitted to me Dein had not been keen to attend in any event. So if such a committee, which can provide parliamentary privilege enabling people to make serious allegations that cannot be done elsewhere (which proved very useful for Lord Triesman and the Sunday Times), then how much more limited are the powers of FIFA? FIFA may act as if it is a state but it has none of the powers a state has, nor the sort of powers Select Committees have.

So once Warner resigned it had to close shop on him. But the ham-handed way FIFA presented it made it appear as if it had exonerated him.

And this is where FIFA, and Blatter in particular, needs to show humility, something that has been in serious short supply in FIFA. This was the reason why it had such a long fight with the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA). FIFA insisted its procedures on drug testing were superior and caused such headaches WADA felt it was one of the most difficult sport organisation it had to deal with. Blatter has also claimed that FIFA’s own Ethics Committee rules are superior to those of the IOC, and it is more transparent. In the light of the corruption scandal, this now sounds risible.

Blatter would do well to learn from Juan Antonia Samaranch, who in the wake of the Salt Lake City crisis, openly admitted the limitations of the IOC and how it cannot match that of a state. FIFA needs to do the same.

If it does not, then the fact that FIFA still has many, very fine people working for it, will get lost. Here, the evidence given by Guy Oliver to the Commons Select Committee is worth noting.

Oliver, who produces an Almanack that bears the moniker of FIFA.com, says he is “not an apologist for FIFA and that they do not exert any editorial control over my work”.

In his written evidence, he is very critical of the England bid, calling it arrogant, but admits, “I am not in a position to say whether the workings of the FIFA Executive Committee are corrupt or not.”

His most significant point is: “What I can be sure of is that the everyday working of FIFA by their hundreds of employees is anything but corrupt. Indeed, I have never dealt with an organisation that does everything quite so strictly by the book. This is where the real work of FIFA is done and to ask if FIFA is fit for purpose to run football, as many MPs have done, this is where you should be examining and not the Exco.”

The problem is, organisations are judged, not by the many who are good, but by the few who are bad, and how the leaders deal with them. News International has learnt that to its cost. FIFA and Blatter need to heed that lesson. Otherwise, for all that the Ethics Committee might do, FIFA will be branded as a not fit for purpose organisation and call for its reform will grow. Blatter may well find himself in the unenviable position Rupert Murdoch is now in.

Mihir Bose is one of the world’s most astute observers on politics in sport and, particularly, football. He formerly wrote for The Sunday Times and The Daily Telegraph and was formerly the BBC’s head sports editor. Follow Mihir on twitter.