Some thoughts on Euro 2020:

● Yes, a 24-team tournament is too unwieldy for most European countries to take on; but it is simplistic to suggest that this alone forced UEFA’s hand, necessitating the adoption of Michel Platini’s Grand Experiment – a competition spread around the great arenas of the European continent.

Turkey, pipped at the post for Euro 2016, could have coped with the expanded format and would, I’m sure, have hosted a terrific festival of football.

But having a single bidder – as, to all intents and purposes, did FIFA for the 2014 World Cup – is never ideal for the rights-holder: it all but ensures the future host holds the whip-hand in competition-related negotiations.

On this occasion, Istanbul’s bid for the 2020 Olympics and Paralympics – a bid that looks, at present, to have at least a 50:50 chance of success – posed an additional complication.

It was these two elements taken together, rather than doubts over Turkey’s capacity to handle a 24-team tournament, which, I would surmise, prompted UEFA to reach the conclusion it did.

● Rather than the anointment of the solitary candidate, we now, of course, have the prospect of an exciting year-long bidding contest, starting in March, as stadia across the continent vie for a piece of the Euro 2020 action.

The process may turn out to have some similarities with the way in which communities in Platini’s native France (and beyond) are chosen to play a part in the Tour de France bicycle race, whose route changes every year.

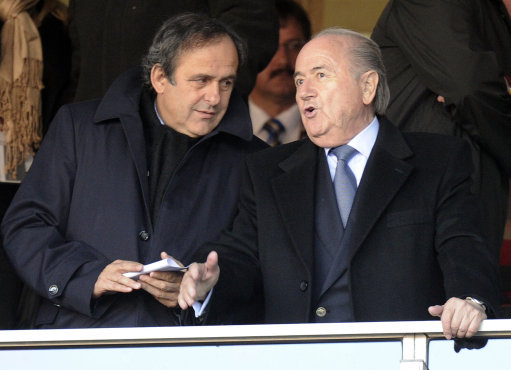

With venues expected, at present, to be selected in spring 2014, one wonders whether the process might impinge on the race to succeed Sepp Blatter (pictured below, left with Platini), FIFA’s long-standing President, in world football’s top job in 2015.

For this to happen, first Platini would need to run – which I think he will; second, the stadium choices, or the whole concept of a continent-wide competition, would need to have a bearing on voting decisions.

For now, this is just another potential element to factor into an already complicated FIFA equation.

But, with other European candidates for the top job a distinct possibility and Platini vulnerable, in my opinion, to being branded the “anti big football business” candidate, I wouldn’t be surprised if the structuring of Euro 2020 played some part in a campaign that will be of critical importance for the future shape of world football.

● The decision to go with a continent-wide format is fantastic news for the Football Association (FA).

The sport’s oldest governing body is already set to benefit from the windfall of seeing two Champions League finals in quick succession (2011 and 2013) staged at Wembley.

The 2011 final generated additional turnover of £16 million ($26 million/€20 million) for the FA, offset by £11 million ($18 million/€14 million) of extra costs.

Now it has been handed an outstanding chance of hosting some big Euro 2020 matches – including possibly the final – as well, and hence of making further inroads into the debt-load it took on to finance Wembley (pictured above) in the first place.

The football authorities in France, the Euro 2016 host, also have reason to be pleased about UEFA’s groundbreaking initiative.

It ostensibly gives them a chance of hosting matches in two consecutive European championships – and given the infrastructural improvements being made with Euro 2016 in mind, French stadia ought to be able to make a compelling case for being handed Euro 2020 ties.

● I have read that the multi-country format will be good for airlines.

This may be so, but it is too early to be sure.

What we may get – though I very much hope not – is a competition in which all the biggest countries get to play multiple matches at home.

● As a student of the Olympic Movement as well as football politics, I find it interesting that UEFA is spreading one of its flagship tournament’s far and wide at a time when “compactness” – how close the venues are together – is held to be a virtue in Olympicland.

I have to say, I think we are a long way from a continent-wide Olympics – although it would make little odds to the vast majority of the event’s sofa-bound, TV-viewing audience.

But it could provide a solution to one of the modern Olympic world’s most intractable problems: identifying a viable long-term business model for Olympic Stadia.

As we know, demand for 80,000-capacity athletics arenas is extremely limited; yet the stature of football club capable of filling such a stadium week in week out on the whole doesn’t want its pitch surrounded by a running track, and does want lots of posh seating for corporate entertainment purposes.

A European Olympics could see the Opening and Closing Ceremonies at (say) Wembley, with athletics entrusted to one of the established Diamond League venues, supplemented with temporary seating to augment capacity.

No, I can’t see it happening either.

But I doubt UEFA will be the only sports body driven to re-think its competition formats in quite radical ways by external forces of which the anaemic European economy is just one.

David Owen worked for 20 years for the Financial Times in the United States, Canada, France and the UK. He ended his FT career as sports editor after the 2006 World Cup and is now freelancing, including covering the 2008 Beijing Olympics, the 2010 World Cup and London 2012. Owen’s Twitter feed can be accessed here.