“Never was anything great achieved without danger.” Niccolò Machiavelli

Perhaps Machiavelli’s death in Florence in 1527 came too soon for him to have enjoyed the popular 16th Century Florentine game of Calcio but you sense he might have been drawn to its brutal tactics and narrative. His modern kindred spirits certainly seem to enjoy the football we love today. Heck, Henry Kissinger was even a board member on the USA 2022 bid committee.

Part of football’s greatness is its exposure of its protagonists to some form of danger. The mixture of the bellicose and the balletic satisfies the spectator’s visceral cravings for conflict and creativity. There are as many crunching tackles as coruscating turns and sometimes these can put players’ limbs, if not their lives, at substantial risk. Arsenal alone know this better than many football clubs.

In May 2006 a now-forgotten 19-year-old Sunderland player by the name of Dan Smith dislocated Abou Diaby’s ankle, rupturing ligaments; two seasons later a wild tackle by Birmingham City’s Martin Taylor snapped Eduardo da Silva’s shinbone and dislocated his ankle; two seasons after that Aaron Ramsey’s leg was broken in two places by Stoke City’s Ryan Shawcross.

These incidents cast shadows longer than those that clouded the individual victims’ lives as their shattered bodies were slowly repaired. Diaby’s injury is the exception that proves this rule as there was not enough time for its collateral effect to be felt. It occurred with only two games of the League season left to play, and therefore had little impact on the club’s overall seasonal performance.

Indeed Arsenal subsequently overhauled a four-point deficit to finish in the Champions League-qualification places but that owed more to Tottenham Hotspur’s implosion in those two games than to their own form. The later Champions League-final defeat to Barcelona was a result more of the goalkeeper Jens Lehmann’s red card than to the disruption to the season of Diaby’s prior injury.

However, with about a third of the season still to play, such injuries appear to have a more profound impact on a team’s performance across the season.

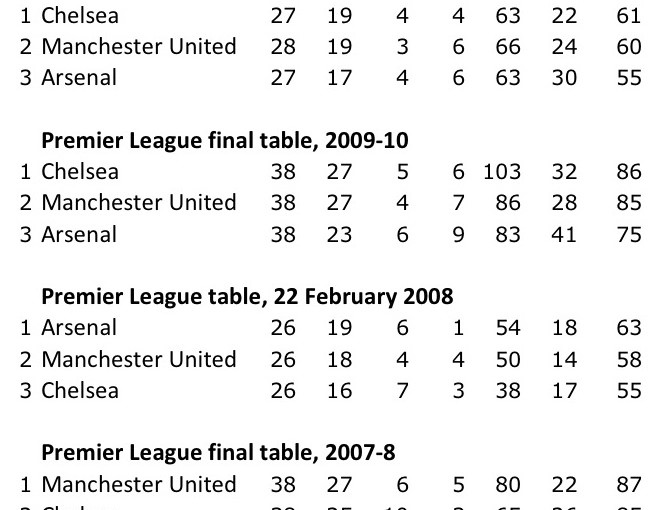

Figure 1: Arsenal’s Premier League positions before and after season-ending injuries to players. Source: Statto.com

In the 2009-10 season, and despite defeats in January and February to both Chelsea and Manchester United, Arsenal still had a slender chance of winning the title when Ramsey was injured. But this was soon extinguished after their midfielder’s season was prematurely ended on 27 February 2010: a points average of 2.04 per game prior to the injury fell to 1.82 afterwards, seeing Arsenal drift to 11 points off the title pace.

After 23 February 2008, when Eduardo suffered his broken leg, the effect had been even more pronounced. Having previously set the title pace with a five-point Premier League lead courtesy of a 2.42-points-per-game record until the end of February, a slump then coincided with his injury. It saw Arsenal pick up only 1.67 points per fixture, leaving them four points behind United in third.

Such on-the-pitch disappointments carry a significant financial impact to the club affected by the injury. Arsenal’s revenues from the Premier League’s performance-related merit award in 2007-8 were almost £1.5 million lower than those to its winners, Manchester United. Having qualified as champions to the Champions League, United took €7.5m more than Arsenal from UEFA’s market pool the following season.

The financial impact between finishing first and third in 2009-10 had grown, to £1.6 million from the Premier League merit award and €10.44 million from UEFA distributions. Naturally there is no way of knowing whether Arsenal would have won the title had Eduardo or Ramsey been available when history records they were not. But the financial impact of not having won it is clearly quantifiable.

Football is a performance-related business and its cliff-edge events can affect clubs far more dramatically than the difference between first and third. Not qualifying for the Champions League at all in 2010-11 would have cost Arsenal a minimum of €21.633 million in guaranteed prize money (rising to a minimum-potential €36.333 million for an English winner).

This takes no account of the millions lost in match-day income as three to six extra home games would not be played if not in European competition, or at least revenues would come at a reduced level from the Europa League. As England’s and Europe’s football-broadcast markets mature, paying ever more to their most successful participants, the cliff-edge events will become only more precipitous.

This is all in the context of the very clear relationship between wages paid and on-pitch performance, as many studies have demonstrated. Confidential data show the relationship between the availability of the best-paid players and seasonal performance is still more significant.

So the elite club suffering such injuries might reasonably seek ways to recover the millions of pounds and euros in income lost through injury to an important player or players. In other industries, businesses would approach the insurance markets for such recoveries.

Were you to own a portfolio of hotels that included one in Florida it would be reckless not to be insured for the asset value of that premises should a hurricane hit. For a certain premium, this could also provide for the potential loss of income related to the loss of the business.

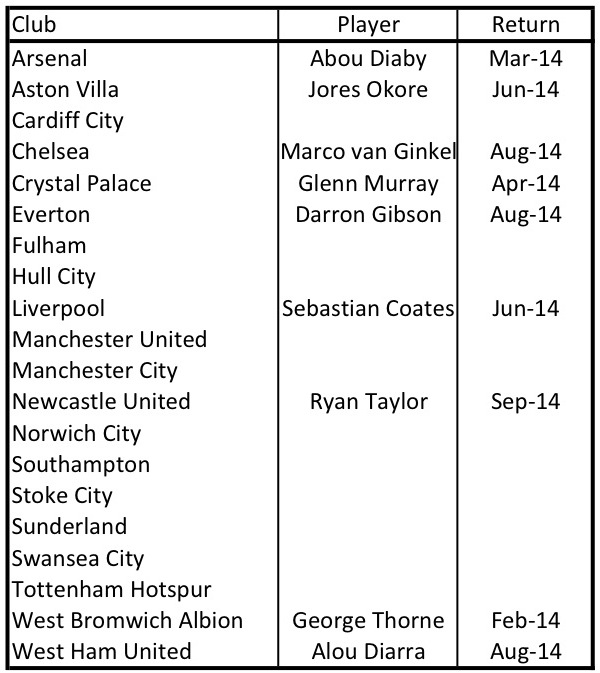

Yet generally speaking, the insurance market has never offered such asset-related insurance should players reap the whirlwind of Hurricanes Smith, Taylor or Shawcross. Indeed for player injuries or illness to affect a club’s season they need not necessarily be out after being on the wrong end of a ‘leg-breaker’. Currently nine Premier League players are out for effectively an entire season having suffered anterior cruciate ligament injuries, one of the most serious a footballer can endure.

Figure 2: Premier League players currently unavailable after anterior cruciate ligament injury. Source: physioroom.com

What football insurance has hitherto covered clubs for is only the wages payable to players who are absent from selection due to long-term injury or illness. (Insurance for catastrophic events such as those that wipe out substantial numbers of players is available, as is the insurance that ends a player’s career altogether. But given the riches available to them from the game, very few succumb to injuries and retire, whatever the impact on their playing performance.)

This means the insurance that has been available to clubs is unfit for purpose. First, a player’s wages over the course of the season are already budgeted for; the fact he has been injured does not raise the cost incurred. Second, the club that claims on insurance for the lost wages is often picking up only a fraction of the replacement cost of the player; however meaningful his wages, a top forward player for instance will have a much greater transfer value. Footballers at the top end of the game are often worth much more in asset terms than income-producing Florida hotels. Yet, essentially, they are the same thing.

The value of any commercial premises resides in the income it produces. Similarly, as football becomes an ever-more-sophisticated business, whose clubs’ executives are increasingly drawn from the worlds of high finance and industry, purchasing decisions over players are also reviewed in such terms. At base, the equation goes something like this: “If we spend £35 million on that striker and another £7 million a year for four years on his wages, will he deliver the club more than £63 million of income over the period?”

Clubs’ incomes, as seen above, often relate to prize money from finishing positions in competitions but the corollary of merchandising and match-day incomes is also factored in to the process. Thus, every single player at every single club has a quantifiable value to that club that is possible to denominate in financial terms. This value makes him a commodity against which an effective insurance policy can be drawn.

This is what Avoca Elite Sports recognised when it devised an entirely new insurance product for football. Backed by a consortium of insurers and reinsurers including Munich Re, Swiss Re and Axa, and led by Hiscox, for the first time ever Europe’s top clubs will each be offered up to £100 million of cover for players suffering long-term injury or illness. The implied effect on clubs’ incomes from lost revenues deriving from these mishaps will be factored in to the insurance at the point of negotiation between the policy-holding club and the insurer over the player’s value. These individual negotiations occur prior to the insurance being taken out.

“Clubs’ turnover and on-pitch performances are correlated, so how they do over the course of the season is affected by the quality of available players,” says Andy Carvill, Avoca’s chief executive. “If key players suffer serious injury or illness then clearly the club can’t expect the same level of team performance.

“This affects income from performance-related streams like the UEFA Champions League’s and Premier League merit awards based on final league position.”

The product could have a big palliative effect in these days of Financial Fair Play. Whereas in the past injury to top players might prompt a moneyed and munificent owner to purchase new models in the next transfer window, a club must in the FFP environment operate within its own resources. Emergency investments are not now so feasible.

“Serious injury or illness to a star player, or maybe a group of senior players, could create a significant financial issue,” added Carvill. “Broadly speaking ‘FFP’ only allows clubs to spend what they can afford, but players are often a club’s most valuable assets. Without the right insurance cover, the club may not have the balance-sheet capital to replace the talent in a like-for-like way or to mitigate lost earnings.”

For although a common criticism of FFP is that it crystallises the elite order of clubs making it impossible for others to break in, the counterpoint is that the consequences of dropping out of that elite due to random injury or illness are more severe than ever. Lose your place in the Champions League and you lose out on tens of millions of pounds and euros of income that could have been put to good use on the pitch.

So, twice a week, clubs are putting tens of millions of pounds of human assets into the firing line on the pitch, where reckless tackles or awkward turns can precipitate a chain of events that ultimately results in the entire business model effectively collapsing.

Machiavelli might have been right when he said nothing great was ever achieved without danger. But he of all people would have liked the idea of spreading its impact around a few insurers willing to take on the risk.

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is now a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him at moc.l1745111034labto1745111034ofdlr1745111034owedi1745111034sni@t1745111034tocs.1745111034ttam1745111034.