“History… is the lesson and the example of the future,” Alphonse de Lamartine, Antar.

As one year rolls into another there is only the fading memory of what came before and an anticipation of what might be. Football’s cycles work to a different calendar, but it is worth considering how the lessons of 2013 might provide examples for what the future will hold in the second half of the 2013-14 season and beyond.

Lesson 1: Money changes everything

With the first half of the 2013-14 season completed, or at least all but completed, the reigning champions are setting the pace in all of the big-five European leagues bar one: England.

What is different about England this year is the amount of money given to clubs from central distributions from Premier League broadcast and commercial incomes. A 70% overall increase in payments to clubs has brought about significantly increased investment in playing squads.

English clubs have always spent large sums in the transfer market to improve their first teams but now the investment has been more broadly spent on strengthening the ‘depth’ of the squad. This means that, rather than to invest merely in the first XI (a strategy that risks being exposed by injuries or suspensions), clubs are addressing the quality of the players who will act as substitutes from the bench or provide more general cover.

There is a strong correlation between wages paid and league finish but it is strongest in what is paid to the 11 who play most frequently. Given the formula for Premier League distributions, the reinforcement has come not only at the top end of the league but throughout. With £2.23 billion (up 55% from the previous three-year cycle) of overseas broadcast incomes being shared by all 20 clubs in equal measure, irrespective of league performance, all clubs have been able to address the deficiencies in their squads. This has brought about some interesting results on the pitch, with newly promoted Cardiff City beating Manchester City and the bottom club, Sunderland, inflicting only the second defeat of the season on fourth-placed Everton. Defeats at home for the defending champions, Manchester United, to West Bromwich Albion and Newcastle United were respectively their first against those clubs since 1984 and 1972.

With the middle- and lower-ranking clubs becoming so much more competitive it has led to a compression of the Premier League table that has not been seen in the other top European leagues.

Figure 1: Spain

Figure 2: Italy

Figure 4: Germany

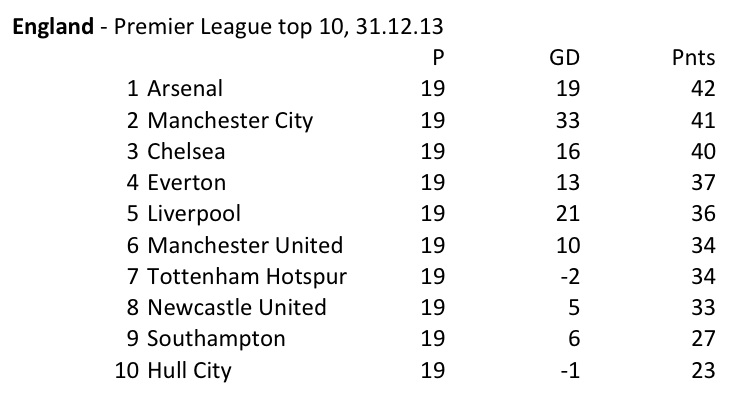

Figure 5: England

In Spain, France and Italy 13 points separate the top and fourth-place clubs, in Germany the difference is 12 but in England it is only five. Indeed, 12 points do not even separate first and eighth, where Newcastle lie only nine points behind the leaders Arsenal.

According to data compiled by Professor Jose Maria Gay de Liebana, a Spanish football-finances expert, Levante played in the 2009-10 Primera Liga on a budget of only €5 million, Hercules on only €5.8 million. The following season Barcelona took in 90 times more at €450.7 million of revenue; Real Madrid almost 96 times more with €479.3 million. If this kind of divergence has endured over the past four years (and it has certainly not been eradicated) then it might call into question the claim on the Liga BBVA official website that it is “la mejor liga de fútbol del mundo”.

The competitively balanced English experience gives pointers to what might be encouraged in other competitions, because a large part of what compels us to follow football’s topsy-turvy narrative is its uncertainty of outcome.

Lesson 2: Football is in a bit of a fix

Uncertainty of outcome, it turns out, is not by any means guaranteed. Across Europe from Ankara to Zaragoza, clubs and players have been accused of unseemly practices in pursuit of glory or riches. Whether to appease club directors who seek to preserve their clubs’ top-division status not by fair means but foul, or to propitiate bookmakers and betting markets with preordained events and outcomes, football is being subverted before our very eyes.

The arrests of several allegedly involved in an international match-fixing ring operating in English football will tell the world much about their murky modus operandi. But even if the British justice system’s severest permitted punishments are meted out to the alleged protagonists it will certainly not end the practice.

For that to happen the offshore system, wherein the ill-gotten gains of the cheats are concealed from the prying eyes of regulators, must be shut down. And given its utility for so many other purposes (not by any means only, but by all means including, the concealment of the graft of business and political elites) there is as much chance of that happening as of Hercules lifting the Primera Liga title.

Lesson 3: Soccer’s Americanisation is inevitable

When the Jacksonville Jaguars’ owner, Shahid Khan, took over Fulham in July, he became the sixth US-billionaire owner of a Premier League club. Fulham, like Arsenal, Aston Villa, Liverpool and Manchester United (but not Sunderland) are a member of the European Clubs Association.

That is the assembly of elite European clubs where the likes of AS Roma (James Pallotta and associates) and Internazionale (the US-educated Indonesian Erick Thohir) are under the ownership of groups with US backgrounds. There is a very different model of sports ownership in the US, where relegation does not exist and clubs share revenues in an even-more-equitable manner than the Premier League.

This has often been described as a “socialist” model for football in the US, with its proponents delighting in how anomalous this is for what is supposedly the land of the free market. But such terminology is entirely misplaced. In European football, the labour element of the economy – the player – draws the lion’s share of its revenues whereas the capital element – the club owner – is frequently subjected to devastating losses; meanwhile the consumer – the fan – gets what he is given. This is far more recognisable as a Marxist approach than that of the US, where franchising permits consumers an element of choice, salaries are capped to restrict labour’s gains and the absence of relegation ensures owners draw substantial guaranteed capital from their businesses.

There is a much-more-stringent level of financial regulation in the US, and it is interesting that the introduction of UEFA’s Financial Fair Play directives has coincided with the billionaires from Wall Street increasingly engaging with the European game. In a world where the labour element of all mainstream economies has increasingly been losing out to the capital element – ever more quickly since the financial crisis struck in 2008 – this could very well be a first step towards a closed-league system for Europe’s elite that is more akin to the NBA’s, NFL’s or MLB’s than what has existed here for almost 150 years. Because if you own a top football club, you do not need to be a US billionaire to recognise how that is in your own self-interest.

Lesson 4: Epochal change is never easy

If a week is a long time in football, which very often it is, then 27 years is long enough for the Jurassic period to become the Cretaceous, or at the very least for the Tithonian age to pass to the Berriasian. Of course no one could accuse Sir Alex Ferguson of being a dinosaur – he was far too cunning for so blundering a label – but his departure from Manchester United’s dugout was a defining event that extinguished him from the top of English football’s food chain.

English clubs appear to have spared themselves the difficulties of replacing long-serving managers by never giving them the chance to establish themselves in the first place. With Ferguson gone, of the 92 clubs in English football Arsène Wenger is now the most entrenched, with 17 seasons at Arsenal’s helm. Paul Tisdale has spent seven at Exeter City, Chris Wilder five at Oxford United and Mark Yates four at Cheltenham Town. Apart from those four, not a single one of the other 88 has spent more than three seasons in charge of his club. Indeed, though David Moyes only took over from Ferguson at Old Trafford in May, there are now 32 clubs whose managers who have spent less time in their jobs than he. It suggests that the fear of relegation described in Lesson 3 currently bears heaviest on the longevity of managerial contracts.

How will Manchester United fare financially without Ferguson? They will be fine, even if they fail to reach the Champions League next season. Lesson 1 tells us of the fabulous riches available even to the sixth-place team in the Premier League, and any club that can boast an official medical systems partner, an official savoury snack partner and an official paint partner, all paying millions of pounds for the privilege of sponsorship, has a sound revenue cushion.

Where United should fear the future is if they face an extended period of reduced incomes following weakened team performance, perhaps due to unforeseen injuries to both their main strikers, Robin van Persie and Wayne Rooney, at once. If a combined £70 million of playing assets were to fail at a time when United were unable to draw Champions League revenues then UEFA’s FFP rules would make it hard for them to invest heavily in an effort to recover a top-four position. United, with their official logistics partner, their official global moving partner and official integrated-telecommunications partner in Malaysia (whatever they may be) are the lucky ones since their incomes are not predicated on team success alone.

Lesson 5: Football needn’t be such a risky business

They 2013-14 season has seen a rare innovation in the business of football with the launch of a new insurance product called Maxi (http://www.insideworldfootball.com/matt-scott/13674-matt-scott-big-injuries-can-mean-big-money-lost-call-your-broker). Clubs can now protect themselves from the impact of losing star players by purchasing asset-protection cover that pays out when they become unavailable. Footballers are no longer employees alone, as their transferable value ensures they have a multimillion-pound impact on clubs’ balance sheets.

Yet few other businesses expose their most valuable assets to such intrinsic risks as the two-footed tackle or awkward fall do a football club’s. Thankfully, at a time when the banks have brought the financial system to the brink of collapse, to the cost of clubs who are finding finance ever harder to come by, this is one financial innovation that should have football directors’ boxes cheering.

Lesson 6: Creativity is not for the pitch alone

Five years in to the financial crisis and football, like most industries made up of small- to medium-sized enterprises, has found credit hard to come by. This has forced clubs across Europe to become creative in how they access the liquidity needed to invest in their businesses.

Third-party ownership has been one route [http://www.insideworldfootball.com/matt-scott/13844-matt-scott-faceless-offshore-funds-and-the-mafia-funding-football-s-have-nots] another has been the mafia. But clubs need to be creative not just about how they borrow but also about how they earn their money. Almost every club carries a brand more powerful than its revenues reflect, and the opportunities for generating income in a connected, social-media world a growing.

Fans hate the phrase but clubs should give more thought to how to exploit their brands with marketing and merchandising partnerships and how to make better use of their fixed assets with more creative, seven-day-a-week use of their facilities. These things have been second nature to the US investors who have seen such value in sports businesses and in this at least it is time for Europe to catch up.

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is now a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him at moc.l1745115017labto1745115017ofdlr1745115017owedi1745115017sni@t1745115017tocs.1745115017ttam1745115017.