“You’ll never have me in your grasp, not in this chariot, a gift to me from my grandfather Helios, to protect me from all hostile hands.” Euripides, Medea

When the infanticide Medea, the original theatrical villain, is lifted with the bodies of her murdered children from the scene of her crime by the sun god’s chariot there is a sense of dissatisfaction about the outcome of Euripides play. It’s a bit of a cop out of an ending, all things considered.

The audience wants justice, and the deus-ex-machina intervention of a higher power to assist Medea in her archetypally selfish act cheats us of it. Ultimately, we all want others to play fair, because we all want the best for ourselves, and the ancient echoes of Helios and Medea’s offence against natural justice still exist today.

The human instinct to act in one’s own self-interest is reflected in all businesses and in football most visibly. If in as rapaciously a competitive industry as football participants attempt to make the playing field a little bit uneven to favour their own ends, then their motives are surely understandable. Most fans do not like it when Ashley Young simulates contact to win a penalty kick but if you are a Manchester United supporter you are more apt to forgive him because the penalty benefits your team. (And, naturally, Young is by no means football’s only diver: most fans should be able from their own experience to see both sides of the coin.)

The European Commission recognises these selfish instincts and the flipside desire for natural justice when it says: “A company which receives government support gains an advantage over its competitors. Therefore, the Treaty [on the functioning of the European Union] generally prohibits State aid unless it is justified by reasons of general economic development.”

It was this element of European law that was being brought to bear when last month it identified what it believed might be a deus-ex-machina intervention from the Spanish government towards the clubs Valencia, Hercules, Elche, Real Madrid, Barcelona, Athletic Bilbao and Osasuna.

The alleged breaches of the Treaty’s principles were specific and complex. In Madrid’s case it is alleged there was apparently “a very advantageous real property swap with the City of Madrid”, the Commission claimed, as well as an exemption from the 30% tax rate applicable to all other clubs than Barcelona, Bilbao and Osasuna (who like Madrid are member-owned societies). Valencia, Elche and Hercules might all have gained advantage from alleged state guarantees behind loans used to purchase shares in the clubs.

Although the EC does not elaborate, the capital raised through the equity purchases was presumably used to make the clubs more competitive on the pitch. If the cases are proved, they would seem to be prima facie examples of state aid benefiting clubs’ on-pitch performance in a country that could ill afford to extend such support.

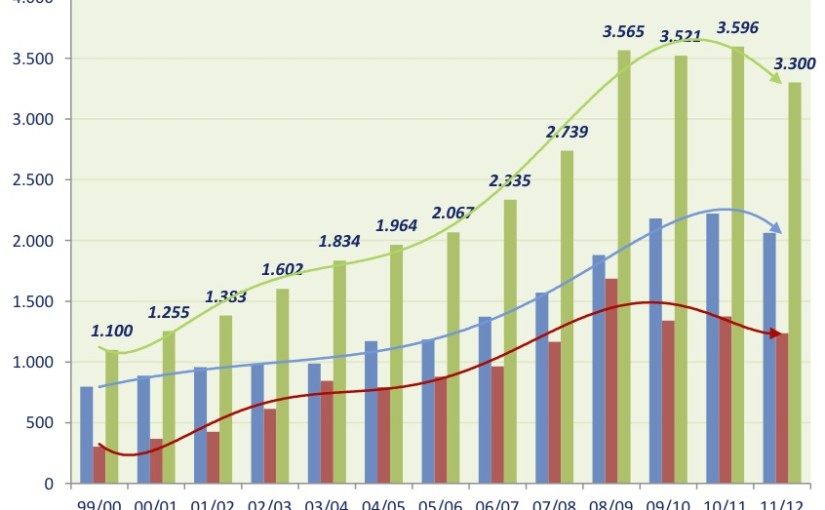

In its study Balance de la Situación Económico-Financiera del Fútbol Español 1999/2012, Spain’s ministry of education, culture and sport found that combined debts in the Primera Liga stood at €3.3 billion.

Spanish top-flight football clubs’ debts 1999-2012

And when the minister of education, culture and sport, José Ignacio Wert, met with Spanish league officials last April to announce a tax-debt reduction plan, it was revealed that combined tax debts in the top-two divisions had reached €673 million. This means that more than one in five of all euros owed by Spanish clubs was due to the government.

According to the Bank of Spain’s own figures the nation’s public debt stood at €954.9 billion last September. Thus 0.07% of Spain’s entire balance-sheet deficit could be paid off at a stroke if its football clubs were to settle their tax liabilities. Were they to do so, it would save perhaps €2.5 billion and more a year in debt-interest payments on their bonds.

No wonder the EC, whose entire financial system has been imperilled by the indebtedness of its non-core economies like Spain, has begun to pay close attention to the profligacy of its professional football clubs. Yet there is resistance within the Spanish government to the EC scrutiny. “The government will fight to defend Spanish clubs because they’re also part of the Spanish brand,” said the foreign minister, José García-Margallo y Marfil.

This is of course ridiculous. Spain might have exited the European Stability Mechanism bank-bailout scheme last week but the message sent by García-Margallo, himself a former tax inspector of all things, is far from healthy. If so high-profile a firm as Real Madrid should be permitted a tax loophole, what incentive is there for the hard-pressed ordinary citizen or businessman to pay his or his company’s dues to the taxman? If Valencia’s fan owners were allowed to default on a state-guaranteed loan to the club, why should the struggling mortgage-holder keep up with his payments to the bank?

What makes García-Margallo’s comment even dafter is that it is not even a populist stance: the fans of Spanish clubs at large seem to support the EC investigation. They see the abolition of the socio model with the 1990 Sports Act as being the root of Spanish football’s financial problems. “The 1990 Sports Act forced the overwhelming majority of our clubs to become professional corporations, multiplying debts by more than 30 times and besmirching them in scandal,” said the Federación de Accionistas y Socios del Fútbol Español, a Spanish football-fan and -shareholder organisation.

The fans would prefer to see the 1990 law overturned, in an effort to return all clubs to the old membership model. It is one that UEFA’s president, Michel Platini, would also encourage. “Members’ societies controlled by socios, who have their own ground, who invest in the youth system and who maintain their own identity, [are the perfect model],” Platini was quoted as saying by El Mundo Deportivo.

But that seems a distant utopia; the weight of the clubs’ debts, combined with the likely demands of incumbent owners to sell, would likely make the biggest clubs unaffordable for most fan groups. The agreement between the football authorities and the Spanish education, culture and sport ministry will see 35% of television revenues remitted to the taxman from the beginning of the 2014-15 season.

This all comes at a time when pay-tv revenues are diminishing: between December 2011 and June last year almost one-in-seven of all pay-tv subscriber households in Spain gave up their satellites and set-top boxes. With incomes falling, cash-outflow demands rising and the State safety net withdrawn, where will clubs now turn?

For Spain’s biggest clubs at least, the answer is towards ever-richer benefactors, just as it has been in England’s Premier League. A case in point is in recent developments at Valencia, where the Singaporean billionaire Peter Lim is said to be preparing a bid to take the club off the hands of its biggest creditor, Bankia. Shortly before their recent match against Real the club’s president, Amadeo Salvo, announced Lim was prepared to pay off Valencia’s €306 million debt to take control. A close associate of the highly influential agent Jorge Mendes, doubtless Lim recognises a brand that would one day make up the numbers in a European Super League should one be set up. And with access to Mendes’s network of third-party-owned players there would surely be other ancillary benefits.

With patient, sustained investment a €300 million takeover of Valencia would then one day look like a bargain purchase. And at a time when there is still a fair degree of shareholder-capital flexibility in the early-stage Financial Fair Play structure, Lim’s money could prove transformative for the 11th-place Primera Liga side. So although it might not be State aid that aids them, Valencia will still be receiving “support [which gains it] an advantage over its competitors.”

And it all adds up to this: when you have game-changing wealth like Lim’s you do not have to be Helios the sun god to be a deus ex machina in football. It is just that when government cash is not involved, there is not a lot the competition can do about it.

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is now a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him at moc.l1745112053labto1745112053ofdlr1745112053owedi1745112053sni@t1745112053tocs.1745112053ttam1745112053.