“Is any of the opposition around?” “Not in any condition to be worried about.” Donald ‘Red’ Grant in conversation with James Bond, From Russia With Love

When Roman Abramovich pitched up at Stamford Bridge with his whirlwind takeover in 2003, few people outside Siberia or the oil-and-gas sector of industry and banking had ever heard of him. But in the decade since his unlikely transformation from governor of Chukotka to guv’nor at Chelsea, the secretive oligarch has become a celebrity the world over.

He has never given an interview but as he has sat in his exclusive box at Stamford Bridge the expressions on Abramovich’s now-familiar face have been shaped by events in the arena below like a Roman emperor’s in the Coliseum. Success is greeted with an indulgent smile; the scowl that meets defeat has often presaged the extermination of yet another soul in the dugout below.

Not that success has been hard to come by for this Roman. In his first season as Chelsea owner, Abramovich had to witness Arsène Wenger’s Arsenal proceed through an entire league campaign without losing a single match. Beating their London rivals in the Champions League quarter-final was scant consolation for him when losing to Monaco in the last four. As Arsenal fans celebrated their flawless title triumph, they paraphrased Chelsea fans’ own chorus: “Chelsea / Wherever you may be / You ain’t got no history…”

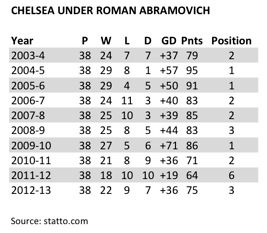

The refrain died with the commencement of the following season as, fuelled by Abramovich’s petrodollars, Chelsea would soon make their own history. The 95 points Chelsea obtained under Jose Mourinho remains a record today. The following season’s 91 points has only ever been exceeded one other time, by Manchester United’s 92 points in 1999-2000.

But it could all have been so different at Stamford Bridge. Years of overspending had preceded the Russian’s arrival, without a plutocratic benefactor to support the club financially. With £29.056 million more cash spent than generated in the 2000-1 season and £13.688 million in 2001-2, Chelsea were in danger of “doing a Leeds United” and collapsing. Using borrowed cash to invest in players – about £30 million net in 2001-2 and 2002-3 – proved a failed gamble, with a sixth-place finish in 2001-2 and fourth the following year. The insolvency specialist, Trevor Birch – himself a former professional footballer – was recruited as chief executive to restructure the club and was pedalling hard to save it.

Bruce Buck knows this better than most. He has been at Abramovich’s side throughout the success-laden past decade. An M&A-specialist lawyer, his prize for advising Abramovich in the abortive 2003 merger to Yukos of Sibneft, the oil firm the Russian then controlled, was the chairmanship of Chelsea, which he retains today. But prior to Abramovich’s July 2003 takeover, Buck has explained, Chelsea had been within days of possibly defaulting on their £75 million Eurobond, payable at an 8.875% interest rate.

“They had a £75 million Eurobond outstanding and it was perfectly clear to the markets that they might have trouble making the July payment,” wrote Buck. “Trevor Birch had been in discussions for some time about restructuring that bond. The financial community as opposed to the football community knew there were some real issues.”

The numbers at stake were always big, and it would take a man of Abramovich’s means to put the club on an even keel. The £30 million-a-season player-trading investment of the previous seasons had proved inadequate, so he invested more. No less than £100 million more. In that whirlwind first season of the Russian’s ownership, £131.050 million was invested in new players after sales, with the likes of Arjen Robben, Hernán Crespo, Claude Makelele and Peter Cech bringing a new sheen and a new spine to Chelsea.

With acquisitions of new subsidiaries and the part-repayment of the Eurobond, Abramovich supported the investment with £240.548 million of new loans. It began a trend of substantial subsidy that has not abated since.

If the trend continues this season it is wholly possible that Chelsea will have received £1 billion in cash from Abramovich over the course of the past 11 years. Given that Forbes estimates him to be worth US$10.2 billion (£6.16 billion) that is an eye-watering sum, even for him. And as things stand it has very little prospect of ever being earned back.

At the end of the 2003 season, and before the takeover, Chelsea’s revenue was £109.934 million. The investment of the first year under Abramovich contributed to a significant (39.74%) increase in turnover to £153.625 million. In the following nine completed seasons revenues gradually grew to £255.772 million (132.66% up on 2003), yet only very seldom did this new income cover the club’s cash running costs.

In terms of operating cash costs at least (as opposed to player trading), Chelsea’s previous regime under Ken Bates had run a tight ship. This model was immediately abandoned too. Year one of the Abramovich turned the 2002-3 operating cash inflow of £16.694 million into an outflow of £17.247 millon in 2003-4, a negative swing of £33.941 million. This was due principally to a doubling of the wage expense from £57.251 million to £110.922 million, although the disposal of the legacy travel-agency element of the business removed between £7 million and £13 million of potential revenue against previous years’.

Winning the title in 2004-5, combined with a £10.591 million drop in the wage bill (one can only marvel at what all those departed- travel agents must have earned) reduced the season’s cash outflow for running costs to £1.756 million. Then the annual operating deficits ballooned. In 2005-6 Chelsea spent £29.093 million more than they earned, even before the £85.425 million net transfer investment. The next year it was £6.121 million, in 2007-8 it was back up to £21.513 million, then £16.120 million the year after. Finally, for the first time under Abramovich, Chelsea broke even from an overall cash perspective in 2009-10, the £11.660 million operating-cash deficit covered by £15.455 million in net transfer receipts.

It did not last long. A £5.522 million cash outflow in running costs in the trophyless season of 2010-11 became an overall cash deficit of £72.170 million once transfers were factored in. Then it was £27.278 million in 2012 (and £78.318 million overall), before another cash-flow break-even last season, of £1.234m, was again shattered by £71.954 million of net transfer investment.

Contributing to all these operating-cash deficits have been £67.669 million in compensation payments to managerial and coaching staff given the thumbs down by Abramovich. Another £25.5 million of compensation went to Umbro for the early termination of a kit-supply deal. But these have been exceptional costs (however routine parting company with managers may appear at the court of Abramovich).

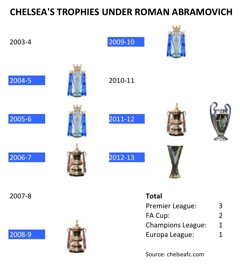

Running a football club incurs more general cash costs like agents’ fees, utility bills, travel, hotels and the like. There are also infrastructure investments, tax and loan interest to be paid for and, even without these last few bits, all told Chelsea have overspent on wages, transfers and other general expenditure by £717.43 million in the decade under the Russian. That, by any measure, is a whole lotta love. Even so, surely Abramovich would consider the expenditure worthwhile. For over the years his club have won so many trophies it has been as if the opposition were not in any condition to be worried about.

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is now a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him at moc.l1745112351labto1745112351ofdlr1745112351owedi1745112351sni@t1745112351tocs.1745112351ttam1745112351.