“Riches, one may say, are like sea-water; the more you drink, the thirstier you become.” Arthur Schopenhauer, Aphorismen zur Lebensweisheit

It was in 1851 that the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer wrote his Wisdom of Life. At the time European empires bestrode the globe and an upper class of landowners and industrialists dominated the social landscape within nations. A militaristic thirst for still more riches brought about the conflict of the Great War, which in turn begat the devastation of World War Two.

For almost half a century after that seismic tremor in history, a more equal social equilibrium was found within the Wars’ principal participant nations. Income distributions in the West were not quite what they were in the Soviet Union but the great disparities of the 19th Century were much reduced. Yet this was a temporary anomaly brought about by the mortal sacrifice of two generations of men. It had never been the natural order, never the human condition.

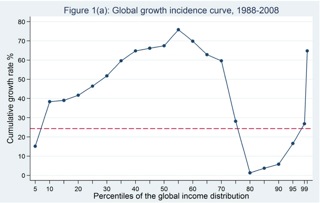

Today, as the chart below illustrates, a return to that more traditional social system has begun in the Western world. The middle classes of the old G7 rich nations (who sit between 75% and 95% on the income scale) have seen incomes stagnate and reduce. The incomes of the richest 1% have risen in a hockey-stick-vertical line. In the grand scheme of human history such divergences are nothing new.

Source: The World Bank

Indeed it is the behaviour of consumers, expedited by technological innovation, which has made this concentration of wealth possible. An unprecedented period of consumption was fuelled by an explosion in household debt. Servicing that debt led Western middle classes to have less disposable income available in 2008 than 20 years before. The financial-services industry that facilitated all the borrowing boomed.

Consumer purchasing habits also contributed to the disparity between the bottom of the upper quartile’s growth rates to that of the top centile’s. It is simpler to jump in a car and head to an out-of-town Walmart than to purchase groceries one by one from individual family sellers on the high street. Inevitably this has concentrated wealth among the new commercial landscape’s winners.

Globalisation, too – clearly a force for good among the 10% to 70% of the world population by income, those in developing nations, who grew exponentially richer between 1988 to 2008 – has accelerated the accumulation of wealth among the top 1%. As has the internet: Amazon sells as easily to customers in Melbourne as in Massachusetts. And so the old order is now the new normal as disparities in wealth have grown and hardened. It has affected every aspect of life, and every last corner of the globe.

Now our industry is joining the march of the elite. When Deloitte announced its annual review of the top clubs’ turnovers last month in the 2013 Football Money League, the second page was devoted to only 13 words. “Revenues for the top 20 clubs grew 8% to €5.4 billion in 2012-13.”

That is an awful lot of Schopenhauer’s sea-water, and the aphorism the German philosopher set out is soon to be repeated: Europe’s richest 20 clubs already thirst for more. Indeed as technology develops and the nature of the football consumer changes, just as it has in the general retail world, there is nothing to stop football’s top 1% joining the party and slaking their thirst like students at a free bar. Their revenues will spike just like they have for equivalent market leaders in all the other walks of life.

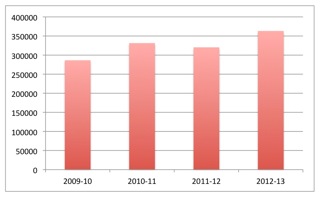

Let’s take a look at the overall turnover of Manchester United, the richest club in the world’s richest domestic league, over the past four completed seasons.

Manchester United turnover 2009-10 (£000)

That is a rise of almost 27% over the period (or about 8.5% a year). None too shabby at all. But how that income has broken down over time tells still more about the rising importance of those who are already football’s wealthiest.

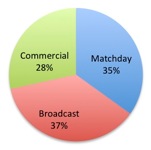

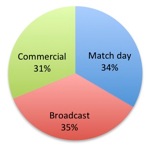

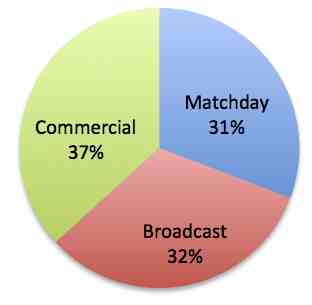

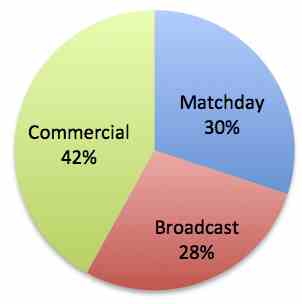

Manchester United income distribution

2009-10

2010-11

2011-12

2012-13

The growth of United’s commercial income as a proportion of turnover has far outpaced that of other segments: it has risen by 87.2% to become considerably the most important area of United’s activity. This reflects how the club has gone from being a local or national business into a true global brand.

The biggest clubs are billboards for the biggest corporations and as such their fortunes are now increasingly tied with those who have benefited most from the shift in global income distributions. European football’s penetration into the increasingly consumerist middle 10% to 70% of the world population by income – the growing middle classes in ASEAN nations for instance – has already translated into a substantial rise in the commercial income of Europe’s elite clubs.

But how will the accumulation of wealth by football’s elite manifest itself in future? It seems that became clear when the Barcelona vice-president, Javier Faus, said on February 3: “We want to see the Champions League expanded and at the same time national leagues should be reduced from 20 clubs down to 18 or even maybe 16.”

Although Faus did not articulate the consequences of such a reduction, these had already been set out more than two years ago by his former boss at Barcelona, Sandro Rosell. “It’s something all of them would have to agree to,” he said in November 2011. “That includes the Premier League, who would have to reduce from 20 to 16. We want a bigger Champions League and hope one day we could play perhaps Barcelona versus Manchester United on Saturdays. That’s what we are aiming for.”

This is not some mad vanity project aimed at supplanting domestic football for the sake of it but a clear and calculated strategy aimed at delivering what the biggest clubs’ customers want. And, callous though it might seem, as the customer base shifts increasingly away from the footprint of the stadium towards the corporations of Wall Street and the living rooms and bars of faraway countries, the demands of the match-going fan will necessarily diminish in relative importance to the clubs’ activities.

But it is not match-going fans alone who face change in their circumstances. Just like the rich world’s middle classes, those top-flight clubs who slip into their nations’ second-tier competitions due to the shrinkage of the best domestic leagues will suffer a substantial downturn in their relative incomes. Gate revenues in the lower leagues may similarly fall if European club football moves to a Saturday (although this is by no means guaranteed) in a shift that would be aimed at satisfying international television markets.

Given how this might impact on its members’ interests the European Professional Football Leagues body has been remarkably quiet on the issue. A call and an email to its spokesman, Alberto Colombo, were not returned. One of his colleagues did engage and implied the concentration of Europe’s football riches into the hands of the top 1% was not the objective of all the biggest European clubs but only Spain’s.

Given reports of a new law in Spain limiting the television income Real Madrid and Barcelona may receive over their Primera Liga rivals to a multiple of four, that might be a logical assumption. However, others have led me to believe this desire is far deeper and more widespread than only in the Spanish and Catalan capitals. Faus’s comments seem intended to plant the seeds for all of Europe’s richest clubs.

That said, and despite the desire to hold international club competition at the weekends, as articulated by Rosell, Faus was careful to underline that it would not be at the cost of domestic football altogether. “We are not in favour of national leagues being eliminated as they are at the centre of fans’ hearts and I can’t imagine that ever happening,” he said. Let us hope Faus’s imagination is accurate.

There is nothing wrong with thirsting for Schopenhauer’s sea-water riches – history has shown how it is the most natural human condition – and, as they say, a rising tide lifts all boats. So if the market is offering commercial returns then they should be exploited. An enlarged Champions League therefore seems inevitable. What matters though is how those riches are exploited, and interested parties like the EPFL should not stand by until it becomes too late.

If there are substantial commercial gains to be made, then the proceeds should not accrue to players and club shareholders alone but also to the match-going fans who create football’s unique stadium atmospheres. This can be done in the shape of discounted ticket prices. There should also be meaningful distribution mechanisms providing the poorer clubs with incentives to develop the talent who will feed the elite clubs in years to come. There must also be regard for football’s social responsibility, since over-borrowed governments do not consider encouraging participation or developing facilities to be their duty; without healthy roots our industry’s head would die.

In football terms today, just as geopolitically it did 100 years ago, Europe stands at a crossroads. A managed and transparent transition, taking account of the wants and needs of all affected parties, is to be encouraged over aggressive expansionism. For history shows that always results in conflict.

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is now a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him at moc.l1745112251labto1745112251ofdlr1745112251owedi1745112251sni@t1745112251tocs.1745112251ttam1745112251.