“Inflation is unjust and deflation is inexpedient. Of the two perhaps deflation is, if we rule out exaggerated inflations such as that of Germany, the worse; because it is worse, in an impoverished world, to provoke unemployment than to disappoint the rentier,” John Maynard Keynes, Essays on Persuasion

Whether or not you have heard of John Maynard Keynes, and whatever you might think of the orthodoxies (libertarians mostly consider him a false prophet of the dismal science, by the way), the long-dead economist is the key figure in the global economic system today.

At least broadly he is: the quantitative easing and fiscal stimulus he recommended should be deployed in recessions were supposed to be directed at programmes to encourage employment, stimulating growth and consumer spending in a modern economy. Instead since the Great Recession began in 2008 these resources have been used to purchase insolvent nations’ sovereign bonds and recapitalise insolvent banks. This has led to speculative asset bubbles in property and equity markets that have done nothing to cure the underlying economy.

Still, it is in Keynes’s name that current government and central-bank policies have been adopted, as it was he who rightly identified how economies as awash with debt as ours should tackle deflation with all available tools. And although the outcomes are not as Keynes would have desired, it is with good reason that extreme measures have been adopted.

According to European Central Bank data updated last week, 57.3% of the euro area’s gross domestic product derives from the expenditure of household consumption, so people’s ability to spend is vitally important to economies.

In a deflationary environment prices fall. This might seem a good thing. But if people stop buying things in the expectation of cheaper goods down the line, firms face cash-flow difficulties, wages become unaffordable and employees are laid off. Unemployment rises and debts can neither be paid nor the interest serviced. The economy seizes up altogether.

This is the situation most of Europe risks experiencing. The continent’s sovereign-debt crisis in 2011 and 2012 seems a long time ago, belayed as it was by the European Central Bank governor Mario Draghi’s statement it would do “whatever it takes” to save the euro.

Sovereign-debt yields – the interest rates governments must pay on their borrowing – have eased across Europe. But although the crisis abated, it does not require a high interest rate for debts to become unaffordable. As Andrew Balls, deputy chief investment officer at the global bond fund Pimco, explained to the Financial Times: “If you have your nominal yield over your nominal growth rate, that doesn’t make for stable debt dynamics.”

Following an extended period of low-to-nonexistent growth, the European Central Bank is now preparing to mobilise itself with its own quantitative easing. These are desperate measures indeed. And if this is the prevailing environment, then it suggests the ECB fears deflation will strike Europe, with a major implication for the continent’s debt.

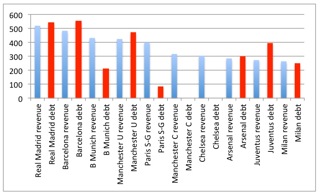

Let’s take a look at the debt levels around European clubs.

Top-10 clubs by revenue

NB: Paris Saint-Germain debt figure relates to 2012 only

Petrodollar-funded clubs like Manchester City, Paris Saint-Germain and Chelsea are notable by having little or no debt at all. Bayern Munich, the current European champions – benefiting as they did from the 2006 World Cup and a healthy subsidy for the construction of the Allianz Arena – have gross debt that is less than half their annual revenues. If investment in everything but wages were pared back as close to zero as possible then it would take Bayern little more than a year or two to clear that debt altogether.

But as the chart shows, all the rest of Europe’s top-10 sides had gearing of 100% or higher in their 2012-13 season in terms of their debt-to-revenue ratio. All this debt is troublesome if, as the prevailing economic circumstances suggest, we are heading into a period of deflation.

This is due to two principle difficulties here. Not only will the debts grow in nominal terms due to the growing relative value of each borrowed euro, but also the ability for clubs to take money from traditional revenue streams will be limited. After all, it follows that if Europe’s general consumer economy is suffering from an unemployment-creating deflationary depression, the amount the unemployed general consumer can afford to pay for entertainment like pay-tv subscriptions and season tickets is reduced.

(Having said that, football can draw heart from the fact that it was never more popular than during the depressed 1930s. If clubs are nimbly flexible with their expenditure – that is to say, their salary commitments – then they can commensurately reduce their demands from paying customers and still potentially thrive as long as their debt is managed effectively.)

There is no uniform reason as to how clubs’ debts have been accumulated. Clubs like Arsenal and Juventus bear theirs as a legacy of their new income-producing stadiums, Manchester United from their 2005 takeover. In truth it matters little why it was raised; its presence on the balance sheet and the terms on which it is financed is what really counts.

Intriguingly some clubs have already recognised the impending danger of a deflationary depression and taken sensible protective measures. Arsenal have aggressively reduced their debts over the past five years, at a considerable cost to their ability to invest in the transfer market. What remains are £219.2 million of fixed-rate bonds, payable at 5.1% per annum interest, and £10.2 million owing to fans at 2.75% per annum interest; the remaining £14.4 million due to fans is interest free. Although this should all comfortably be affordable for as long as Arsenal’s incomes are at 2012-13 levels (which are set to be lower than those over the next 12 months at least), it would not be a surprise if the board continued to take steps to reduce them ahead of schedule.

Manchester United have also adjusted their borrowing profile to meet future economic challenges. Until September 2012 United’s borrowings were overwhelmingly in bonds with coupons (or fixed interest rates) of between 8.375% and 8.75%.

The board was evidently spooked by the deflationary threat that would cause the nominal value of these interest rates to rise in relative terms and it has placed an enormous bet to protect itself. The debt-profile switch has cost United a one-off payment of effectively £33.8 million but it has significantly adjusted the interest payable. Now the English champions’ borrowings are held in floating-rate loans, using the controversial Libor rate as the index, and with a premium of between 1.5% and 2.75% per annum on top.

These could turn out to be important safeguards for Arsenal and United and, although other European sides’ debt profiling is less transparent than that of the English clubs, it would be wise for other highly geared sides to follow their lead. Still, as Balls pointed out, unstable debt dynamics do not derive only from the yields paid on those debts but also from the lack of growth in revenues the borrower can achieve.

Again, European deflation is very bad here. But there are ways for the top clubs to avoid its consequences, and it is to be expected that these will be exploited in the years to come. This column considered last week how the vaulting divergence in wealth between Europe’s richest and its traditional “middle class”, coupled with the emergence of a new, richer stratum in developing nations, would likely translate into a coalescence of the top clubs into a closed elite league (as forecast by the Barcelona vice-president, Javier Faus).

I will not rehearse the arguments here but it is clear that the threat of a deflationary economic environment only makes that outcome still more likely. This is because highly indebted European clubs would not be able to sustain their borrowings as they have in recent times. As a result, either they pay those debts down aggressively (which most have not done in the past) or they chase new revenues through a new elite-league competition.

Football administrators and club boards everywhere should begin to position themselves accordingly, because it is going to happen. But those who now attempt to restructure heavy debts should take care what terms they accept from their lenders.

Manchester United, usefully, took out new loans that can be repaid at any time, apparently without the big penalty fees the bonds attracted. This might be the most sensible decision of all.

For if the European Central Bank’s own defensive measures against deflation – QE and likely fiscal stimulus – substantially overshoot their inflation targets and in time it looks like we are moving into an inflationary period such as that seen in the 1970s, then United will probably be able to fix their rates again. That would be doubly useful since at the same time inflation would handily reduce the nominal value of their debts.

That said, for all our sakes, we will just have to trust that the “exaggerated inflation” Keynes recalled from Wehrmacht Germany does not return. For there is no amount of planning a football club can make to protect against that.

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is now a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him at moc.l1745116904labto1745116904ofdlr1745116904owedi1745116904sni@t1745116904tocs.1745116904ttam1745116904.