“Keep your life free from love of money, and be content with what you have,” Hebrews 13:5, King James Bible

How much is enough? It is a question we should all perhaps ask ourselves in pursuit of happiness. According to several passages in the Bible, having enough is simply when your belly is full, whereafter the leftovers should be given to the needy. Trying to convince yourself of that is probably a bit extreme in a 21st Century consumer society but it is definitely a question that should concern those who work for distributive not-for-profit organisations.

The highest profile such organisation in the football world is of course FIFA, which distributes its income from tournaments such as the World Cup in the form of development grants. Annual revenues were announced last week as being $1.386 billion, a record number boosted as they were by the Confederations Cup tournament in Brazil. This generated a $72 million surplus, which boosted cash reserves that now stand at $1.432 billion.

Fans reading those numbers, particularly in terms of the cash reserve, might wonder why there is not a FIFA-branded football pitch on every street corner of the globe. But though it earns FIFA a modicum of interest as it accumulates in some Swiss bank, that cash reserve is not strictly FIFA’s to do with as it wills.

The world governing body is showing good corporate governance by building so bloated a cash balance: it self insures for the possibility of one of its tournaments being cancelled to the detriment of suppliers such as broadcasters or sponsors. The compensation it would have to pay if that eventuality arose for a World Cup would indeed measure in the hundreds of millions.

“It is virtually impossible to find cancellation insurance to cover an event of such magnitude,” FIFA’s annual report makes clear. “FIFA’s current reserves correspond to approximately one-third of total costs for [a four-year] period. Having sufficient reserves is of great importance to FIFA’s financial independence and to its ability to react to unexpected events.”

Clearly, then, $1.432 billion is not yet quite enough. But what of other areas of FIFA’s activity? Kieron O’Connor, a football-finance blogger, suggests FIFA has shown more enthusiasm in recent years for developing its own cost base than for developing the game worldwide.

In a series of tweets on his @SwissRamble Twitter page, O’Connor questioned a number of areas of FIFA expenditure. He drew up a table that shows how FIFA’s staff costs rose 73% between 2008 and 2013, to $102 million. O’Connor shows how over the same period payments made for football development have risen by a considerably lesser degree: 19% to $183 million.

Another area of explosive growth in expenditure has been in “legal matters”, doubling over the period from 2007 to 2013. The size of FIFA’s legal bill is very large indeed: $28 million in 2013 alone. So FIFA spends more on lawyers than on the Goal Programme, more than what it pays to confederations for bureaucracy, what it pays them for development programmes, more than three times more than payments in the refereeing assistance programme and four times more than Football for Hope.

This is because FIFA has a global governance function that many other football bodies, such as leagues, do not perform. That said, it makes up only 5% of FIFA’s activities by expenditure and may not therefore be considered its primary function. (Even so, there are many in the football economy who would prefer that its regulator spent more time, effort and cash on this area of its ambit to clear its lengthy backlog of cases.)

Still, despite this difference, it is worth comparing FIFA’s situation with that of the Premier League, for there are many similarities between the two. Both are football organisations with a global supplier base of overseas sponsors and broadcasters. At £1.285 billion ($2.117 billion) the Premier League’s turnover was about 50% higher than FIFA’s yet by far the overwhelming majority of this was funnelled into the clubs and good causes they support, with very little indeed held back for bureaucracy.

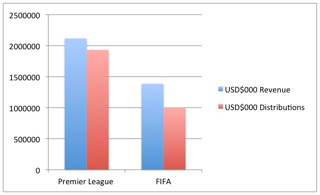

The comparative expenditure on administration in relation to revenues is illustrated below:

Included in the red column for FIFA are the expenses related to its core functions of hosting events (like the World Cup), development expenses in grants and programmes and its governance activity. Together these come to almost exactly $1 billion a year. For the Premier League, the red column relates to distributions to member clubs in prize money and broadcast payments ($1.731 billion/£1.050 billion) as well as payments to such bodies as the Football League ($86.7 million/£52.6 million), the Professional Footballers Association ($28.5m/£17.3m) and the Football Foundation grassroots-facilities fund ($17.8m/£10.8m). In total that all comes to $3.182 billion/£1.930 billion.

Clearly, being a domestic competition, the Premier League does not have to meet certain elements of the cost base the world governing body must. For instance there is no outlay on an annual Congress for the full plenary of a 209-association membership, or on flying officials from all over the world to HQ for committee meetings. But comparing the two organisations’ relative spending gives you the impression that if it did, the cumulative cost would not be $32 million. That is, however, what such trips come to at FIFA.

One area of obvious similarity between the two leagues is in their personnel. Both are staffed by highly skilled specialists in the services industry. FIFA has a headcount of 452, the Premier League 94. FIFA’s higher number of employees reflects its additional obligations that are not beholden on the Premier League. At the Premier League staff earn on average £117,500 ($193,900) a year. At FIFA the mean wage is at a gross level appreciably higher: $225,700 a year, or 16.4% more than the average Premier League staffer’s.

But it is when the two figures are compared on a net-income basis that there is a big difference. According to the Swiss Federal government’s official tax calculator, if the FIFA employee is unmarried, has no children and is on that average salary of $225,700 a year, he will receive a net salary of $178,000. A Premier League employee in similar circumstances on their own organisation’s average salary would take home $118,300, meaning FIFA is paying premiums of more than 50% on its average annual take-home salary over that paid to Premier League staff.

There are obvious flaws to these calculations. First is that declared personnel costs include all the highest earners and all the lowest-paid workers, from president or chief executive down. Second is that most Premier League employees are English, working in England’s capital for an English organisation. FIFA’s international employee base has to be persuaded to move to Zürich, and the hook is likely to be money.

None of this should be read as a polemic of envy. Nor is it intended as criticism of FIFA. It is aimed instead, little more than a year before a new presidential election, as an exhortation for FIFA to pay close attention to its growing general expenditure and relatively shrinking element of contribution to growing the world’s game, one of the principal functions of the organisation. For as emerging-market currencies fall, key FIFA suppliers such as Adidas, who alongside broadcasters underpin much of the organisation’s revenues, are coming under considerable financial pressure as its repeated recent profits warnings have reflected.

In short, FIFA’s revenues have been growing fast over recent years, but it should not behave as if the good times will always roll. With every extravagant expense chit signed off by FIFA’s chief financial officer, with every first-class travel ticket paid for, there is less to share around the football world for its grassroots.

As senior staff of financial-services institutions attending a seminar were recently instructed: “Given the macroeconomic forecast, financial institutions can no longer grow their way out of their problems. Instead, they must make difficult choices regarding their operating models. With top-down support, expense management should become a leading practice and be perceived as a key success factor.”

If even the banks – not known in the recent past for their Christian business practices – are recognising that they have more than enough, it is probably time for football’s governing body to follow suit, for the good of the game.

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is now a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him at moc.l1745640527labto1745640527ofdlr1745640527owedi1745640527sni@t1745640527tocs.1745640527ttam1745640527.