“Your sons and your daughters are beyond your command. Your old road is rapidly agein’. Please get out of the new one if you can’t lend a hand. For the times they are a-changin’.” Bob Dylan

For the past 20 years football has had a very healthy and profitable relationship with pay-tv. This will be underlined once more over the next 24 hours or so when the Premier League makes its announcement over the result of the auction it has being holding for its UK rights. The numbers will be big.

UK and international broadcasters provide around half of all Premier League clubs’ combined revenues, which for the 2013-14 season are estimated to have been £3.2 billion. But about 40% of that cumulative turnover came from that season’s four Champions League clubs alone. Once their revenues are factored out, the total estimated contribution of central Premier League payments to the other 16 clubs’ revenue was around 60%.

It can very much be expected that this proportion will rise still more with the new TV deal but just how sustainable is this model? Although it is the TV companies who write the cheques, the money derives from fans who pay the TV subscriptions. In a deflating world where incomes are falling and debt-service-costs are rising, can the constantly inflating costs of television subscriptions be justified?

That is a question households around the world will be asking as the deflationary economic environment bites in the months and years to come. Over the past 20 years football has boomed with the baby boomers whose disposable incomes after decades of living through bull markets have permitted consumption on an unprecedented scale. But nothing grows to the sky, and as the baby boomers reach retirement age, those replacing them do not have the funds to maintain the level of expenditure of the older generation.

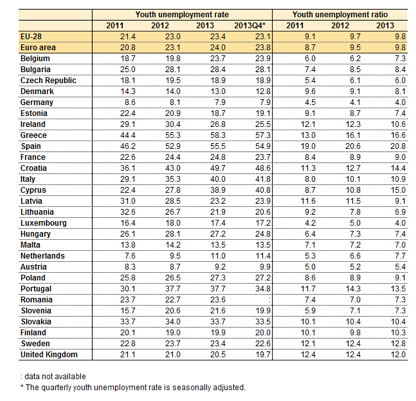

Take a look at the official European Commission statistics for youth-unemployment rates and ratios. The rates in the table below account for the number of people aged 15 to 24 years old divided by the total labour force. The ratios relate to the number of 15 to 24 year olds who are neither in full-time employment nor full-time study programmes. Either way the numbers of those out of work have been growing fast. Across the European Union the number of young people out of full-time work or study rose by 6.6% between 2011 and 2012. It was even worse in the euro area, where it rose by 9.2%.

It is interesting that although in the UK the numbers have been improving (the youth-unemployment ratio is down 3.2% between 2012 and 2013), they are coming from a much worse position than most. Of all 28 EU members, only Greece, Spain, Cyprus, Sweden and Portugal have had worse youth-unemployment ratios than the home of the Premier League.

It is not a great start for those youngsters and it could very well be that they are embarking on lifetimes outside of economically productive society. For them, football in all its professional forms – either at the stadium, on TV, or in pubs and clubs – is likely to be forever out of reach. There are also those older people who are “underemployed”, in only part-time work, of whom there were nearly 10 million across the EU in 2013, with a further 2.2 million jobseekers not immediately available for work and 9.3 million available for work but not looking for it. These economically less active people will also find it ever harder to fund consumption of football.

Many of those in the 15- to 24-year-old age group have grown used to consuming their media for free from websites like the BBC and the Guardian’s, media like the BBC’s Iplayer, music streamers like Spotify. Even highly prized Premier League matches can be found on pirate streams for free in some corners of the internet.

All these things have conditioned many consumers into believing that football can be and should be free. So what will the future economic model for football look like?

When he was the owner of Fulham Football Club, Mohamed Al Fayed claimed the Premier League was not earning enough for its clubs. He believed that the shareholders of BSkyB, the parent company of the Premier League’s core historical broadcast partner, Sky Television, were growing fat on the toil of the rights-holder clubs.

While that analysis was probably grasping and overly simplistic – Sky took on considerable risk to deliver football to consumers – his point that Sky acts as a highly skilled middleman to the consumer is accurate. The Premier League has since launched its own channel, Premier League Productions (for which, to declare an interest, I do some on-screen work).

This in-house programming has opened access to the Premier League for a new breed of broadcasters who would not otherwise have the production expertise to create sports channels: the telephone companies. Firms like BT in the UK are great partners for football rights holders as they have diversified incomes from a number of sources and are not reliant on a single pay-tv revenue stream. They can provide internal cross-subsidy to fund higher bids for Premier League rights, raising the stakes in the auction processes.

By providing a fuller package of programming to bidding broadcasters, it helps broadcasters go beyond the 90 minutes of live action and is a very useful development for the League’s broadcast licensees. But the Premier League prefers not to lead the way in its innovations (its chief executive, Richard Scudamore, tells friends he prefers to “stay one step behind technology”) and has not gone as far in this as has one other rightsholder: Major League Soccer.

MLS used the internet to build hugely successful youth-orientated programming on its KICKTV YouTube channel. Indeed, the channel was so successful that it ceased to be a promotional tool and grew into a genuine commercial venture itself, diverting management time away from the core activity of running a football competition. So last week, MLS signed a deal to spin off the channel to the UK-based digital-content company Bigballs Films to become the transatlantic sister channel to its flagship Copa90 – see related article below. (I must declare another interest here as an occasional consultant to Bigballs.)

The deal is very interesting as a new model for rights holders to consider as they look for growth from fresh revenue streams. Using third-party broadcasters to deliver programming of their live events is one thing, but the opportunity is limited. It is the third-party broadcaster that accrues the added value by monetising all the magazine programming around it. And this means there is tremendous potential value from sponsors unavailable to rights holders.

MLS have had an insight into this through KICKTV and have now engaged Copa90’s producer as the best in class to pursue the future growth opportunity. The Copa90-KICKTV deal also gives us an interesting insight into the nature of the future relationship between fans and the rights holders themselves.

With no access to live rights of its own, Copa90’s success has been built on celebrating fan culture in football. It provides access to the look and feel of everything around live football for a generation of people who, for the reasons explored above, have been shut out of the game they love.

It is what executives at Bigballs call the last yard of engagement with consumers, and the major brands who sponsor football competitions love it. At the same time MLS’s determination to embrace this unique selling point speaks volumes about how it is pioneering a new attitude towards fans that is seldom seen in other leagues around the world.

Where so many rights holders have been rentiers living off the incomes fans provide through season tickets and what they pay broadcasters and sponsors, MLS is pointing the way to a culture that is more conversational, more engaging with football’s consumers.

In a digital future where the old road of commercial success is rapidly ageing, that certainly feels like a good way for football to be a-changing.

Related article: http://www.insideworldfootball.com/football-marketing/broadcast/16303-copa90-buys-mls-youtube-channel-kicktv

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is now a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him at moc.l1745118344labto1745118344ofdlr1745118344owedi1745118344sni@t1745118344tocs.1745118344ttam1745118344.