“I read a stat the other day that Burnley are bigger economically than Ajax.” Richard Scudamore, Premier League chief executive

The announcement that broadcast rights for Premier League football will soon be worth £1.712 billion (€2.317bn, US$2.633bn) every year in the domestic UK market alone must have caused a flood of mixed emotions for club executives across Europe.

Some would have perceived it as the inexorable rise of the Premier League as an overbearing commercial behemoth bent on destroying other competitions’ interests. Others would have taken it as an encouraging reflection of the rising tide in football-rights values in general. The canniest would view it as an opportunity to take some of the Premier League’s cash by selling players to its wealthy clubs.

The truth of the matter is that the Premier League’s success, which will be reinforced when international rights deals are struck later this year, is not unique. Other leagues are growing too, and this much is reflected in the transfer market. It is less than a fortnight since the January transfer window came to a close and the 2014-15 transfer-spending cycle with it. Since then some excellent data have been made available by the Soccerex/PrimeTime Sport Transfer Review.

The document provides insights into the activities over the past 12 months of transfer trading and the longer-term trends that are associated with it. And it is clear that over the years there has been very rampant inflation in the value of players as assets on the clubs’ balance sheets in several leagues, and little or no decline in the others.

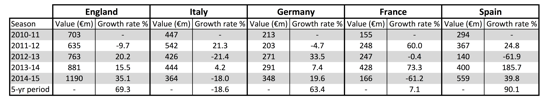

Player-trading expenditure across Europe’s big-five leagues

Source: Soccerex/PrimeTime Sport Transfer Review 2015

This strength of spending signals the robustness of the commercial model across the European game. Now it is possible when using the above data and combining it with the amount of cash spent net (i.e. expenditure on players after sales) to extrapolate an estimate of the aggregate value of players on clubs’ books in each of the above leagues.

The numbers will be very rough as there are a number of inputs that cannot be quantified exactly. For instance, the duration of each player’s contract is here assumed to be four years, when some contracts will be longer, and factors such as the release of players through free transfers cannot be included. But that said, this is roughly what the unamortised value (that is to say how they are accounted for in the clubs’ books) of player assets looks like in the big-five leagues in Europe:

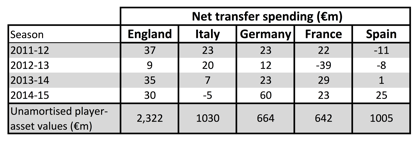

Net transfer spending and player-asset values across Europe’s big-five leagues

Source: Soccerex/PrimeTime Sport Transfer Review 2015 (Net transfer spending); Matt Scott (Unamortised player-asset values)

This suggests the combined current book value of the players across the top-five leagues in Europe is €5.67 billion. If it were spread out evenly then there would be close to €60 million of players at each club across the 98 in Europe but of course it is not. There are large spikes in the value of players at certain clubs, as the table below shows:

Relative weighting of biggest transfer spenders across Europe’s big-five leagues, 2014-15

And all this is just the amount historically spent on players. The market value of those same players might be substantially higher. A player with only two years left on his contract is still likely to be worth more than a club bought him for if he is at or nearing his prime and has been a consistent performer throughout his career. The inflation in player values will almost certainly grow more significant still with the new Premier League TV deal, and all the more so with the influx of fresh cash into the Europe-wide game with the new UEFA Champions League/Europa League cycle that begins next season.

So what impact will this fresh injection of cash have? One effect it seems will be to increase competitive balance. There are currently only five points separating the Premier League’s third- and seventh-place teams. Last season at the same stage the gap was 13 points; the season before it was 10 and for each of the two previous seasons it was 14. There are therefore several clubs who risk failing to qualify for the Champions League, including frequent participants such as Arsenal, Manchester United and Liverpool.

For these clubs the world is changing against them, at a time when the risk of absence from the elite European competition threatens to cost them more than ever: several tens of millions of pounds. If that coincides with the long-term absence of key players through injury then it is a double whammy. In an era of Financial Fair Play, where investment flexibility is reduced by UEFA rules, clubs must rely on their own resources to recover. Yet replacing key players – whose values, as shown above, are ever rising – at a time when revenues are falling becomes tremendously difficult.

At the bottom end of the competition things are similarly tight. Twelfth and 18th places are currently separated by only five points. This time last season those same five points separated 10th and 18th. In 2013-14 it was Norwich who eventually succumbed to relegation, after a succession of lengthy injuries to key midfielders ripped the heart out of the team. The cost to Norwich was catastrophic: what could have been close to £100 million of turnover this season was cut in half at a stroke as they fell out of the Premier League and into the Championship. In such cases clubs move quickly to grab cash and reduce wage bills, selling the most marketable players, further compounding the impact of the relegation.

Yet although so much of this severe impact can be mitigated through adequate insurance protection, most clubs who run the greatest risks – those towards the top end and the bottom end of the competition – carry no cover at all. What they do take is insurance against players being forced into retirement through injury but, as shown in the Norwich example above, it does not take permanent disablement of players to destroy a season.

Relegation is an emotional wringer for all fans but the worst of it for owners is the destruction of capital. Leeds United, one of England’s great clubs, were relegated in 2003-4. It has often been cited as a cautionary tale against the dangers of debt. But it was not debt that caused Leeds to fail on the pitch. It was the loss of players that the unwinding of those debts incurred. Catastrophic injuries or illnesses can have a very similar effect to on-the-pitch performance and once financial hardship hits, the hopes of returning immediately to the top flight could become just as hard as it has been for Leeds.

Premier League clubs are under pressure from fans to reduce ticket prices and distribute more of their income across the football pyramid. Such calls are understandable. But if fans – or, more to the point, owners – of Premier League clubs knew that their participation in the European elite or the world’s richest domestic league was being put at risk through a lack of proper insurance protection, they might think there are other good ways for a little of that new money to be put to use.

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is now a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him at moc.l1751598753labto1751598753ofdlr1751598753owedi1751598753sni@t1751598753tocs.1751598753ttam1751598753.