“What’s yours is mine and what’s mine is my own.” Jonathan Swift, Polite Conversation

By making assets of men, football has always had a unique relationship with property. In no other walk of life can the right to employ someone be a tradable commodity worth tens of millions of pounds, dollars or euros.

It is a fact that has brought much consternation among unionists (who oppose the current football-labour system) and much scrutiny from lawmakers (who helped structure it). It’s not a perfect system but, in terms of balancing the irreconcilable interests of labour movement and contractual stability, it is probably the best we could have.

Where it becomes more complicated still is in the realm of international football. Then the most-expensive properties in the world game are released by those who own them for extended periods in which they are used by other authorities who have intrinsically less care for their welfare.

Traditionally the governing body of the world game, FIFA, has relied on its regulatory powers to oblige clubs to let their players participate in international football tournaments, qualifying matches and friendlies. In the past there was not even a penny’s compensation – the “what’s yours is mine and what’s mine is my own” logic that Mr Neverout employs to acquire a toothpick case in Swift’s Polite Conversation.

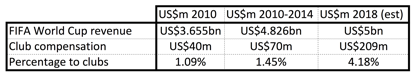

But that has changed in recent World Cup and European Championship tournaments, with clubs receiving restitution from the proceeds the events generate in return for the unquestioning release of their players. At the 2010 World Cup the return to the clubs was $40 million (€36.5m, £26.7m at today’s prices), in Brazil last year $70m (€63.9m, £46.7m). At Russia 2018 and Qatar 2022 it will now be $209m (€190.8m, £139.7m), following an agreement struck between FIFA and the European Clubs Association last week.

Although it multiplies the amounts available to clubs threefold, it is still reasonably small beer when compared to the overall FIFA World Cup revenues generated in a tournament featuring those players, as the table below demonstrates.

According to the accompanying statement from the ECA, FIFA has also made a number of concessions in governance that will permit the clubs’ body to have a say in a number of regulatory decisions hitherto the preserve of FIFA. Among such areas that now fall within the ambit of ECA input will be the International Match Calendar.

Such privileges have been hard won by the ECA and have not been surrendered lightly by FIFA. Over the years it has fought off several prior moves by experts such as its Independent Governance Committee and other interested parties to extend the inclusiveness of its regulations to other football stakeholders such as the clubs. FIFA’s president, Sepp Blatter, is not generally for turning. So what has motivated the sudden volte face?

This column has long warned of the threat of a withdrawal from international football by the employers of the players at the FIFA World Cup [see related article below]. The absence of a memorandum of understanding between the ECA and FIFA left the world governing body susceptible to secession. Such an MoU has existed between the European confederation, UEFA, and the clubs but FIFA was never a signatory. And when the clause relating to FIFA expired after the FIFA World Cup last year, it meant the world governing body was on some pretty dodgy legal ground.

This column can reveal that a case involving the International Handball Federation in Germany last year had given clubs in all sports the upper hand over international associations. The IHF Player Eligibility Code demanded that players must be released for national-federation tournaments including the Olympic Games, world championships and such like. The Code added that clubs who gave up their players to such events would “not have any claim to compensation”.

These rules, argued Germany’s handball clubs before Dortmund’s Landgericht court, amounted to the illegal abuse of a dominant position, something the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union describes as “incompatible with the internal market”.

The court found that when handball players are released by clubs for participation in international-federation competitions, it is “a service that resembles a supply of temporary workers… In an unregulated market, the purchaser of such services cannot expect to get [such] benefits [for free], at least not in the context of a business relationship between companies if he uses commercial ‘contract workers’.” These facts, the court added, “affect the [clubs’] entrepreneurial freedom” and amounted to “gross unfairness or arbitrariness.”

The parallels with a FIFA World Cup system in which only between 1% and 1.45% of the overall competition proceeds flowed back to the clubs were clear. Given that there was also no opportunity for the clubs to have any say in the general governance of matters that affect their “entrepreneurial freedom”, the situation was all the more vexed.

But in football the economics of the situation are naturally far more important than in handball. There is no handball player in the world who has ever been transferred for €100 million. In football there is more than one.

Were the ECA to have pushed back as aggressively against the FIFA player-release regulations as had the handball clubs against the IHF, the result could have been spectacularly damaging for FIFA. Any adverse decision in a court could have threatened the FIFA World Cup and even therefore the very financial foundation of FIFA itself.

And so this fundamental jeopardy explains how, after years of refusal to extend any meaningful engagement to clubs it sees as subordinates to its member national associations, FIFA has for the first time conceded substantial ground in its relationship with such stakeholders. Moreover the payment of $209 million to the clubs provides better recompense for the risk they undertake when releasing their players to international teams.

A public court case would have been an enormous bunfight between some of the most-important actors in the world game, and although that would have been very interesting for all observers, it would not have been particularly seemly for the reputation of football on the whole. The ECA, led in the negotiation by its president, Karl-Heinz Rummenigge, and FIFA, led in turn by Blatter, are to be applauded that the prudent route of conciliation was chosen.

And so consequently, from now on – for a few weeks every four summers and a few competition dates at other times too – FIFA may properly tell the clubs with impunity that “what’s yours is mine and [about 96% of] what’s mine is my own.”

Related article: http://www.insideworldfootball.com/matt-scott/15081-matt-scott-when-money-can-t-buy-peace-how-history-tells-us-a-football-revolutions-is-afoot

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is now a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him at moc.l1745219900labto1745219900ofdlr1745219900owedi1745219900sni@t1745219900tocs.1745219900ttam1745219900.