“Ring a ring o’ roses, A pocketful of posies, A-tishoo! A-tishoo! We all fall down.” Traditional British nursery rhyme

For centuries British children of what we now describe as primary-school age have been singing this popular tune: holding hands and dancing in a circle before falling on their bottoms together. It is widely believed (though it is disputed by some) that the song dates back to the age of bubonic plague, when huge percentages of populations across Europe lost their lives to that terrible disease.

The plague was so pervasive it is estimated to have taken the lives of between 30% and 60% of Europe’s 14th Century population. The key to the devastation it wrought lay in the ease of its contagion and the profound damage the bacteria involved do to human immune systems. Not many of those who caught it pulled through.

Last month this column studied how a catastrophic event, namely relegation from the Premier League, has affected a small sample of clubs who have been unable to recover their status [see related article http://bit.ly/1H57Car]. In financial terms at least, it has been a plague on their houses. Only four of them – Ipswich Town, Derby County, Middlesbrough and Watford – lost a cumulative £120.9 million in cash between them over a six-season period in which they all were in the Championship.

It would be unwieldy to perform a similar six-season study on all clubs who have ever fallen out of the top division, and even that would not tell the full story of what has befallen every relegated former Premier League club. It is, though, reasonable to assume that the destruction of capital involved has widely been repeated elsewhere. But as we approach what is frequently described as the “business end” of the season, I have chosen to look at the statistics of relegation and what patterns emerge. And there are some quite remarkable findings.

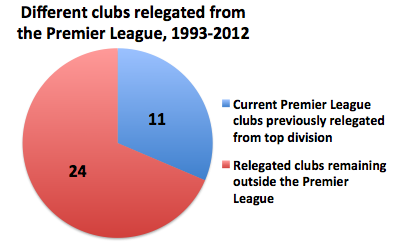

First of all, it is clear that it is easy to fall out of the Premier League. There are of course only 20 teams who currently participate in it, down from 22 between the 1992-3 and 1994-5 seasons. Yet fully 35 different clubs were relegated from the Premier League between its inception in 1992-3 and the 2011-12 season. (I have ended the period under calculation two completed seasons ago and not included the most up-to-date seasons, since it only seems fair to count clubs with a reasonably extended absence from the top division.) Of these, more than two-thirds have been unable to regain their Premier League status, as the chart below illustrates.

There are currently seven Premier League clubs who have unbroken participation in it throughout following its inception more than 20 years ago: Arsenal, Aston Villa, Chelsea, Everton, Liverpool, Manchester United and Tottenham Hotspur. Stoke City and Swansea City have both maintained their Premier League status since first achieving it with promotion in 2008-09 and 2010-11 respectively. Apart from them, all the other clubs currently in the English top division have dropped out of it at some point or another.

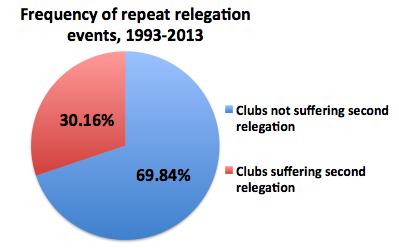

But those who have regained the Premier League ranks are the lucky few when compared to their 24 former peers who are currently finding a return elusive. What is more worrying for those who drop out of it is that the danger of a repeat relegation down to England’s third tier is very real indeed. The table below demonstrates the frequency of clubs being relegated a second time following their initial exit from the Premier League.

It happened 19 times among the 63 clubs to have fallen out of the top division between the league’s launch season in 1992-3 and 2012-13. That is surely enough to worry those clubs who make it to the top that they will end up falling out of it again. One might think that, owing to increases in Premier League “parachute payments” — distributions to relegated clubs — those who go down once are now less likely to be relegated again. But far from it: it is not as if the phenomenon has been eradicated in more recent years.

In 2011-12 Wolverhampton Wanderers were relegated, suffering a second successive drop to the third tier the following season (although they have since returned to the second-tier Championship and are still vying for a play-off place with two games of that competition’s season remaining). Though it is as yet incomplete, Blackpool, who lost their Premier League status in 2010-11, have already been relegated from the Championship this season. It is also very strongly possible that Wigan Athletic will join them this season, two years after falling from the top division, which would be consistent with the almost one-in-three of clubs who suffer that repeat relegation.

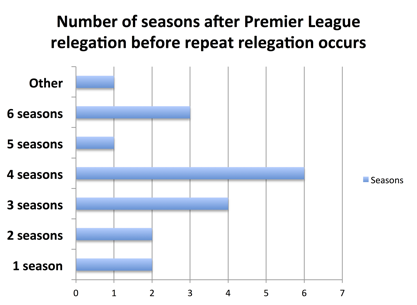

Wigan, though would be slightly unusual inasmuch as very few clubs have lasted only one or two seasons in the Championship before going down again. The bulk of twice-relegated sides, 10 of the 19 so far recorded, have fallen in their third or fourth seasons after dropping out of the Premier League, as the table below demonstrates.

This tells us two things. First that the Premier League’s “parachute” regime, which pays clubs broadcast dividends over a four-year period, has been effective. When the money drops, clubs find it harder to retain their place in the Championship. But survive for seven years in the Championship and there is statistically a better-than-95% chance you will not go down again.

The above charts would also seem to tell us that statistically there is a chance every year that one of the three relegated clubs will find their way down into the third tier of English football at some point in the not-too-distant future. But closer analysis of the trends tells us this is too simplistic an expectation.

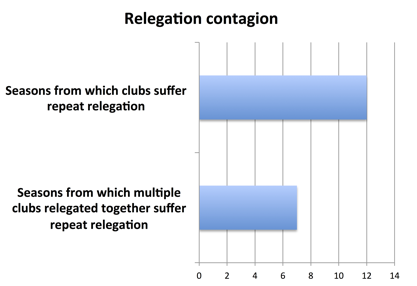

What is most intriguing and unexpected in my analysis is that clubs who fall down do so as if in a ring o’ roses, not individually but hand in hand with another club who shared their relegation from the Premier League. It does not necessarily follow that they do so together in the same season, but what does seem to happen is that the deadweight of one team losing their Premier League status is at some point contagious for one of those who also went down with them.

So if one of the three clubs relegated from the Premier League in any given season goes down a second time, there is statistically a better-than-50% chance that one of those who was initially relegated out of the top division will at some point join them in also falling into the third tier.

This has happened when Oldham Athletic followed Swindon Town in a repeat relegation after their shared Premier League exit in 1993-4. Also when Manchester City were later joined by Queen’s Park Rangers after their 1995-6 joint relegation, Wimbledon and Sheffield Wednesday (1999-2000), Coventry City and Bradford City (2000-1), Leicester City and Leeds United (2003-4), Norwich City and Southampton (2004-5) and finally Sheffield United and Charlton Athletic (2006-7).

Indeed, so frequent has the phenomenon been that the only clubs ever to have suffered repeat relegations in isolation are Nottingham Forest (this happened twice for them following their Premier League exits in both 1992-3 and 1998-9), Blackpool (2010-11) and Wolverhampton Wanderers (2011-12). But in both those latter cases there is still time for their fellow relegated clubs, which were Birmingham City and West Ham United in 2010-11 and Blackburn Rovers and Bolton Wanderers in 2011-12, to join them in succumbing to repeat relegations before they reach the statistically safe threshold of seven seasons.

This all tells us something. Firstly, if you are going to be relegated from the Premier League, you’re only really safe if you go down with Nottingham Forest. But also we can infer that, if as seems likely Wigan were to fall down another league this season following their 2012-13 relegation, then Queen’s Park Rangers (currently 19th in the Premier League) and Reading (19th in the Championship) ought to watch their backs.

Because if you have held hands in relegation with a Premier League club that catches a cold and is relegated again, the statistical chances are pretty high that, one day, you will fall down just like them.

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is now a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him at oc.ll1745641411abtoo1745641411fdlro1745641411wedis1745641411ni@tt1745641411ocs.t1745641411tam1745641411m.