“Since Arsene Wenger arrived in north London, Arsenal are the only team Spurs have not finished above in the whole Football League.” Opta

It was 20 years ago, pretty much, that Arsène Wenger walked through the door at Arsenal. In two of the previous four seasons they had finished 10th and 12th in the Premier League. Located in a beloved but ageing arena hemmed in on all sides by houses preventing stadium expansion, the risks to future performance were more to the downside than up.

What Wenger proved 20 years ago was that good management could transform a club from middling performers into a genuine European contender. However, although he is undoubtedly a visionary and is still to this day one of the finest managers in the game, Wenger and Arsenal were lucky that their marriage began in 1996. For the twin circumstances that facilitated its enduring success are unlikely ever to be repeated.

First, following the decline and stagnation of Liverpool, the dominant English team of the 1970s and 1980s, only Manchester United stood tall in the Premier League. Next, the Champions League was soon to be born, permitting runners-up of national competitions to qualify for entry to the European Cup.

It meant that a duopoly enduring almost a decade would be created, one in which United and Arsenal would share domestic trophies and achievements almost to the exclusion of all others. Wenger’s rivalry with United’s manager, Sir Alex Ferguson, became the dominant media narrative around English football. Attention to the Arsenal brand became more widespread; revenues consequently grew.

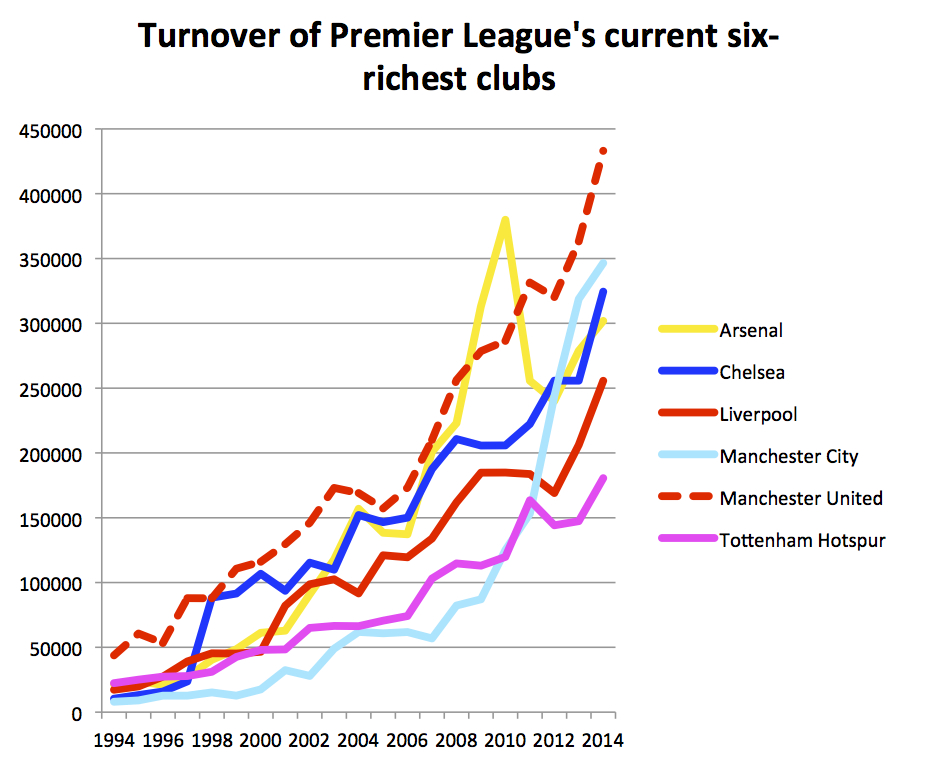

Now, though, mere management alone cannot thrust clubs into the European limelight. With the extension of England’s Champions League contingent to four clubs, what was once a duopoly between Arsenal and United has now become an impenetrable subset of top “multinationals” whose revenues derive mostly not from the Premier League central funds but from blue-chip sponsors overseas.

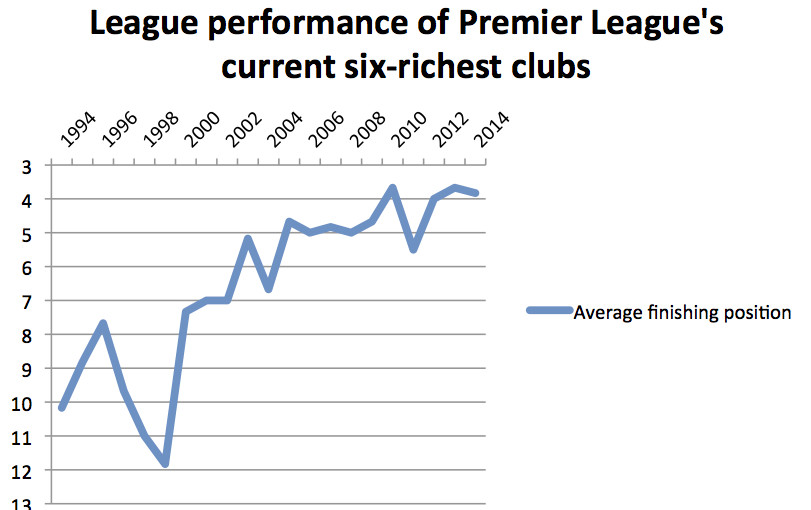

That much is clear from the table below, which reflects the average finishing position of Arsenal, Chelsea, Liverpool, Manchester City, Manchester United and Tottenham Hotspur from 1994 to 2013. It illustrates how the current top six richest clubs have risen to a dominance that is almost completely to the exclusion of all others.

What underlines Wenger’s personal achievement in forcing his club into that early duopoly is how Arsenal were by no means best placed to compete with Manchester United at the top of the Premier League when he arrived. That mantle lay with Tottenham Hotspur.

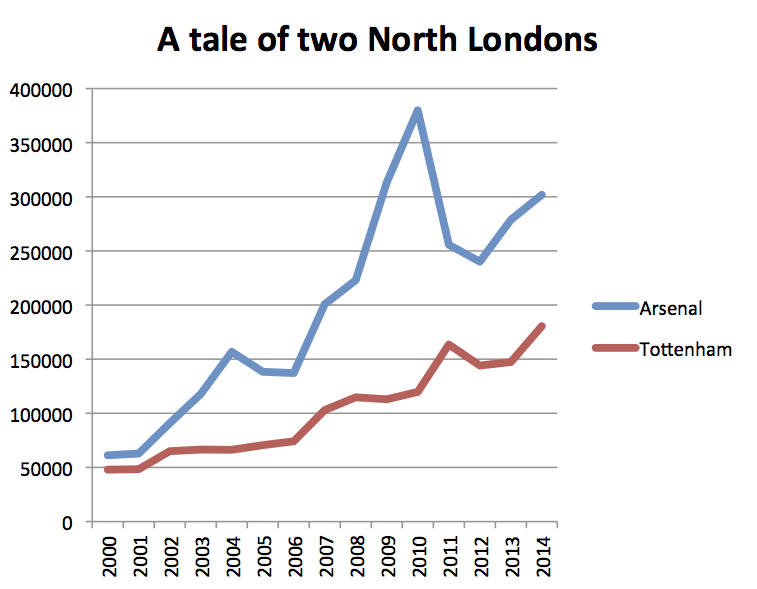

But in the intervening 20 years, Spurs have stagnated financially. Having been the second-richest Premier League side in 1994, Tottenham’s aggregate revenues in the five seasons leading up to and including 2013-14 amounted to £755.4 million. That is not small beer, but it pales into comparison with what Wenger’s side has achieved over the period. Arsenal have generated almost twice as much in that time: £1.459 billion.

This is despite Spurs holding their own against their north London rivals in commercial terms. In each of the past two completed seasons they have generated more than £56 million from sponsorship and retail activities. Arsenal’s revenues from that segment were £77.2 million in 2013-14 and £62.4 million the previous season, figures that could be termed comparable. Although Champions League participation has contributed the bulk of the £30 million difference in broadcasting revenues between the two clubs each year, even that is not what has created the financial gulf.

What separates them, obviously, is what will go down in history as Wenger’s great legacy to Arsenal: the Emirates Stadium. In 2013 and 2014 matchday turnover at White Hart Lane was £33.5 million and £34.8 million respectively. For Arsenal, revenues generated on matchday and from property sales associated with the club’s various Highbury and Ashburton Grove developments were £103.4 million and £133.3 million respectively. As can be seen from the chart below, revenues spiked following the opening of the stadium in 2007 as property sales from redeveloping their old stadium into Highbury Square came on stream.

Now although they will not have such a property portfolio to sell as Arsenal did (they are redeveloping their existing ground, not moving elsewhere) it is understandable that Tottenham’s board, in search of the revenues they have seen their neighbours routinely accrue through their 60,000-seat stadium, want some of that for themselves. But building a 56,000-seat arena of their own will not come cheap. The £49.8 million contract Spurs have signed for the design and construction of the basic structure of the stadium including ground works and foundations proves as much.

Indeed, for Arsenal, the Emirates Stadium project impinged on the club’s on-pitch performance for about a decade. For his club to be in a position whereby they could create their world-leading returns from matchday activities has been a tremendous exercise in restraint from Wenger. Operating on a shoestring budget for new players, he was denied the baubles of the transfer market in favour of melding a team from the bargain bucket. A near-10-year trophy drought ensued.

So surely Tottenham will face the same encumbered fate? Well, no, not necessarily. First of all, as noted above, Spurs are building on their own stadium site. This means they will not tap the property-development revenues Arsenal have enjoyed since 2007 but neither are there any of the complications of the magnitude Arsenal faced. Not only did redeveloping the old-stadium site into flats become an enormous senior-management headache, they also had to move a huge waste-transfer and recycling facility from their new home to another place in London.

Moreover, when Arsenal began work on their project in February 2004, steel was markedly more expensive than it is today. Benchmark prices were around $550 per metric tonne on average over the course of the Emirates’ construction, Spurs can benefit from an environment wherein they cost about $450/MT. Even allowing for a weaker pound today than it was between 2004 and the stadium’s opening in 2007, after inflation that still equates to a steel price below the £300/MT it was 10 years ago. But the big kicker in Spurs’ favour is that the biggest inflation felt over the period has been in what Premier League clubs earn and the diversity in the way they earn it.

Arsenal’s gearing on the £260 million of project finance they required to get the development under way was enormous. So lenders wanted to see vast amounts of collateral from the club itself to help cover their risk. But back then there were really only two or three commercial properties available to a club: shirt-front and kit-manufacture sponsorship and, possibly, naming rights. Arsenal exploited these to the hilt, selling discounted long-term arrangements with Emirates and Nike in return for cash up front. This meant that, as can be seen from the second chart above, shortly after construction started, Arsenal’s turnover fell from £156.9 million to £138.4 million.

With a far-more-sophisticated sponsorship market available to them, Spurs now have the opportunity to sell many more commercial partnerships than were at Arsenal’s disposal back then, meaning that if they must borrow from the future in one area they can make at least some of it up from elsewhere.

Furthermore, the cost of the debt should not be too high. I understand the financing arrangements have already been agreed at a time of record-low interest rates. Arsenal struck an incredibly good deal on the interest rate for their stadium borrowings, but Spurs are unlikely to have to pay a higher coupon.

And their ability to service that debt already seems proven. Despite going on a substantial spending spree after selling Gareth Bale for about £85 million to Real Madrid, Spurs kept a lid on the wage bill. It rose only £4 million, or 4.5%, while turnover rocketed 22.5% – by £33.1 million. This meant Tottenham had operating cashflows of £83.2 million last season, enough to spend a net £43.8 million on transfers and £17.3 million on infrastructure around the stadium. By adding that cashflow to £40 million of preference shares issued to equity holders, Spurs also reduced their borrowings from £54.4 million in the red to a net-cash position of £3.5 million.

Backing all this up is the fact that the current average age of the 11 players Mauricio Pocchettino would likely pick as his first team next season is 23.6 years (although clearly this might change with future transfers). It is a squad that is cheaper to retain – and more marketable in the event of liquidation – than at many other clubs.

But most important of all is the new TV deal. Arsenal’s revenues and ability to service their debts were, in the mid-00s, highly reliant on the Champions League source. Back then, the domestic Premier League TV deal was worth £1.024 billion over three seasons. That has now ballooned to £5.136 billion for 2016-19: a mid-table club might earn £150 million from TV rights alone – equivalent to more than Arsenal’s 2005-6 full turnover.

There is no question there will be some short-term pain for Spurs, that is for sure. Having to spend the construction period away from White Hart Lane – with MK Dons’ temporarily expandable stadium the current favourite to host them – will limit match-day revenues still further. But, once they come out the other side in their shiny new ground, engorged on the corporate revenues it generates, the 10-year period of reduced on-pitch performance suffered by their rivals is unlikely.

Arsenal fans have borrowed the phrase ‘Mind the gap’, a health-and-safety warning the London Underground tells its passengers as they board its trains, to tease their Tottenham peers. But as that gap in financial clout eventually begins to close, the Wenger-era-long period of red-and-white dominance of North London may one day also come to an end.

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is now a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him at moc.l1745229390labto1745229390ofdlr1745229390owedi1745229390sni@t1745229390tocs.1745229390ttam1745229390.