“For the investor, a too-high purchase price for the stock of an excellent company can undo the effects of a subsequent decade of favorable business developments.” Warren Buffett

It’s hard to argue with any of the aphorisms spoken by the most successful investor in modern history. Warren Buffett has made himself a multi-billionaire, and lots of other people very rich too, with his seer’s ability to pick a stock through forensic financial analysis.

He has made his fortune with methods widely described as “value investing”, which involves buying in to a company whose share price is demonstrably lower than the value intrinsic to it. It is not merely about the quality of the company itself, as he points out, it is also about what it costs to invest in it.

These are the metrics those who want to buy in to the football industry today are increasingly applying. There are lots of great clubs, lots also for sale, but will they over time deliver a sound return on investment?

To interrogate this question from a European-wide perspective, I have taken a look at the UEFA club rankings that were released this week. The purpose of looking at these is that qualification into European competition is the readiest way to create internally generated revenues, which in turn is the readiest method of generating RoI.

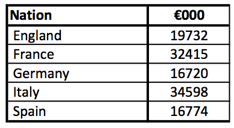

The table below shows the minimum guaranteed revenue for clubs from the big-five leagues competing in the Champions League during the 2013-14 season. This corresponds to the UEFA participation bonus and the individual league’s market-pool payment to the club that entered the competition from the lowest qualifying place in the domestic league. It assumes the club loses all six of its group matches, earning nothing from performance bonuses.

Minimum guaranteed Champions League participation revenue by nation, 2013-14

The base domestic revenue for most clubs outside England, where broadcasting arrangements are comfortably richer than anywhere else in Europe, is sub-€100 million. This means the minimum €16.7 million available from the Champions League constitutes a material double-digit percentage increase in turnover. (And getting results in the competition has great value. In 2013-14 it was worth €250,000 for each draw and €500,000 for each win; progressing out of the group stage was worth a minimum €3.5 million, a quarter-final exit €3.9 million, the semis €4.9 million and the final €6.5 million or €10.5 million, depending on who won.)

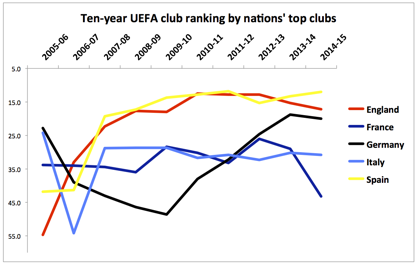

Now it is very clear from the 2014-15 club rankings that the nation with the strongest clubs in European competition is Spain. For the 2014-15 season Real Madrid and Barcelona were respectively the first- and second-ranked teams in Europe, as they were the previous season. The 2013-14 finalists Atlético Madrid rose to fifth from seventh. With Valencia, Sevilla and Villarreal alongside them, the top-six clubs in Spain have a mean European club ranking of 12.0.

That compares to 17.2 in England, where Chelsea are fourth best in Europe, Arsenal ninth, Manchester United 10th and Manchester City, Tottenham Hotspur and Liverpool also ranking. In Germany the mean ranking is 20.0, where Bayern Munich lead the way in third, Schalke are seventh, Borussia Dortmund and Bayer Leverkusen 15th and 16th respectively and Stuttgart are much lower down. Then there is Italy with 30.8, none of whose clubs feature in the top 10, and France – ditto – with 43.2.

But this is a mere snapshot of the European football topography. Stretching back over 10 years’ data we can see how European football dominance has pretty much been spun on its axis – where the top-five of Italy and Germany once were the leagues with the best-ranked top-five or -six clubs, now it is Spain and England who do.

(NB: In the above graph, six clubs were used for England, Italy and Spain, reflecting the more consistent performance of their member clubs over the period than in Germany and France, where only five were chosen. In 2005-6 England’s Tottenham Hotspur and Spain’s Atlético Madrid were unranked by UEFA, as were Atlético and Italy’s Fiorentina in 2006-7. In these cases a notional ranking of 200 has been chosen to reflect their ranking against peers.)

So what does all this matter to the prospective top-division football investor? Well, quite a lot actually, because consistency in the above graph shows the entrenchment of the top-ranked sides in each league. For instance in England, Arsenal and Manchester United have huge intrinsic value as two clubs that have consistently featured in the top 10 across Europe for a 10-year period. Throughout Europe only Barcelona can say the same.

Among the others we can see that the remaining clubs in England have broadly performed consistently well over the course of the 10-year period, similarly in Spain, whereas performances in Germany, Italy and France have been more volatile. Drawing from this, it is clear that in England and Spain, gaining access to the Champions League positions – and the strong RoI that generates – at a club outside the big six is going to be very difficult and/or expensive indeed as both countries yield only four Champions League positions. In a world of Financial Fair Play, it may not even be possible for clubs in England to repeat the feat of Manchester City and break in to the top four.

Indeed, in England competition is so strong that even for those who have been Champions League incumbents, a temporary slip can prove devastatingly costly. As recently as 2007-8 Liverpool, having won the Champions League in 2005 and been finalists in 2007, were the third-ranked side in Europe. However, an extended run outside of the competition beginning with their seventh-place Premier League finish in 2009-10, with only one Champions League qualification in six years, saw them tumble to being the 42nd-ranked club in Europe in 2014-15.

So this helps explain why, despite the fact that several clubs in England, home of the world’s richest league, have been on sale for a frustratingly long time for their owners. West Ham United, West Bromwich Albion, Newcastle United and Aston Villa are only four whose owners have made publicly clear their intention at some point to sell. Privately, comfortably more than half of the Premier League clubs have been on the market for years, yet the last major takeover of a top-flight English club was Arsenal by Stan Kroenke in 2011, and he already had a substantial shareholding anyway.

Yet in the past season alone, Valencia and Atlético Madrid have secured major investment from some of the richest people in Asia, with AC Milan soon to join them. As can be seen from the chart above, the key to those deals has been the relatively cheap access to Champions League football those clubs can provide. Milan is a great club, a great brand that 10 years ago was the top-ranked side in Europe; it has fallen on hard times and so is available more cheaply than a club of commensurate local stature in England or Spain.

The fact is in business, value investing is what matters. It is why the Qataris bought Paris Saint-Germain – the only major club in a major world capital with near-guaranteed access to the Champions League. It is why Marseille or Sevilla would be a better bet to buy than West Brom or Newcastle. And it is why Warren Buffett would not get involved in football at all.

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is now a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him at moc.l1745230901labto1745230901ofdlr1745230901owedi1745230901sni@t1745230901tocs.1745230901ttam1745230901.