“Money, it’s a gas/ Grab that cash with both hands and make a stash/ New car, caviar, four star daydream/ Think I’ll buy me a football team…” Pink Floyd, Money

When in 1975 Roger Waters wrote the lyrics to Money, Manchester United belonged to a local meat wholesaler, Louis Edwards. It was still about 15 years before his son Martin accepted a £20 million (€28.7m, $31.2m) bid for the club from a consortium led by Michael Knighton, a former schoolteacher, although that takeover ultimately collapsed.

How distant seem these times today as the top clubs in England, like most of its historic financial and business institutions, lie in the hands of billionaire foreign shareholders. Even a rock star couldn’t afford United these days. But this column will not be a lament on lost identity or any such nonsense, for the Edwards and Knighton were just as motivated by money as are the Glazers or John Henry and his associates – the colour of their passports is irrelevant. Indeed, satellite ownership has been no hindrance to the value intrinsic to the English clubs, which are by and large the world’s most prosperous.

Columns passim have looked in detail at the commercial segment of the top European clubs’ activities [in particular, see related article below]. But the bulk of those sums are only indirectly contingent on on-pitch performance. So as Manchester United’s hosting of Tottenham Hotspur on Saturday kicks off the new Premier League season, what I want to look at is what stakes the top clubs are playing for during 2015-16.

What is clear is that this season’s Premier League will be the richest title race ever, but not because of what will be paid by the Premier League itself. As the final year of a three-year domestic broadcast cycle with Sky and BT Sport, payments from the Premier League will for this year at least remain broadly flat to those they received from last season’s efforts, give or take a few hundred thousand here and there.

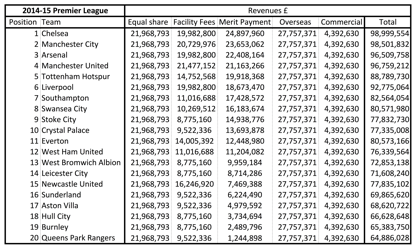

These were as follows:

Source: PremierLeague.com

By and large they were again the highest broadcast payments available to any league in the world, although some clubs, such as Barcelona and Real Madrid, with their individual rights deals, could earn more for themselves. (Although it is of course only going to be a prelude to a still-bigger deal for the Premier League next season, which will rise to £5.136 billion – €7.4bn, $8.0bn – over three years.)

But for all the riches on offer from the Premier League, the biggest driver of new income for the top clubs in this campaign will in fact be what is on offer from Europe. Let’s take a look first at what English clubs have earned in the recent past from the Champions League. The payments made by UEFA for the 2014-15 season have not been publicly disclosed, so we must go on what was paid in 2013-14 for accurate figures. Since they came from the same three-year broadcast cycle these were broadly similar to those from the following season.

UEFA uses a complicated formula to determine what it distributes to clubs from 75% of the gross commercial income it earns (the other 25% it keeps for operating costs and solidarity payments to national associations and clubs). This is based around three main factors: 1) how much the TV deal UEFA has with each club’s domestic broadcaster is worth as a proportion of the gross revenues it takes – this is the “market pool”; 2) the club’s performance in the Champions League that season and 3) the club’s performance in their previous domestic season.

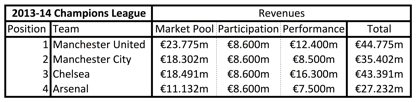

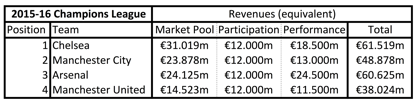

In 2013-14 this worked out as follows:

Under point 3) Manchester United earned the most from the previous season’s achievements, having won the title to earn 40% of the base “market pool” payment. As second-place team Manchester City earned 30% of this element, Chelsea as third-place qualifiers 20% and Arsenal 10% for finishing fourth.

This is not the only factor in the “market pool” distribution, since it is related also to a club’s performance in the Champions League campaign. This is how Chelsea, despite earning a base payment that was 30% less than City’s, were able to recover the difference by reaching the semi-finals when City were knocked out in round two. Obviously, this deeper progress in the competition also substantially affected the amount paid for performance under point 2) above.

So all in all United took €44.775m (£31.245m, $48.756m) City took €35.402m (£24.699m, $38.553m) Chelsea €43.391m (£30.284m, $47.253m) and Arsenal €27.232m (£19.006m, $29.656m) in 2013-14. This was a tremendous bonus to the £60.814m (€87.113m, $94.879m) United earned domestically from winning the Premier League, adding more than half as much again to their football-related revenues.

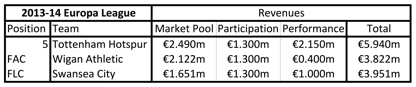

But that said, when comparing these sums with the Europa League, it shows the opportunity cost for Tottenham Hotspur in not reaching the top four was not really all that large. The difference between what Spurs earned from their run to the last 16 of the Europa League (in the table below) and what Arsenal took from a last-16 appearance in the Champions League was €21.292m (£14.867m, $23.194m). That’s a fairly big number, but it is not a game changer for either club.

The new UEFA TV cycle offers new opportunity for the Champions League-chasing clubs in England. The figures below assume identical performances this season for each of the four clubs as they were in 2013-14 – so Arsenal as third-place club are assumed to reach the semi-finals, as Chelsea did in 2014, the reigning champions Chelsea to reach the quarter-finals as United previously did as champions and for City and United to exit at the second-round stage as the corresponding second- and fourth-place clubs did.

This amply demonstrates the new riches available from the BT deal, which constitutes almost a fifth of UEFA’s entire TV revenue for the 2015-16 season. Equivalent performances raise English clubs’ Champions League revenues by between 37% and 40%.

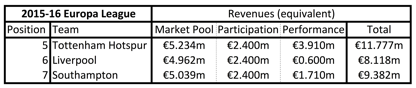

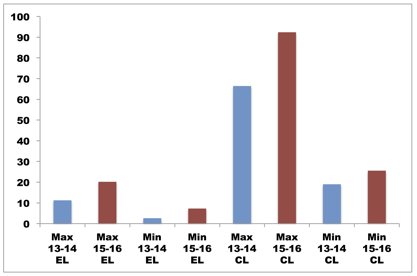

Now this tremendous proportional raise is not as great as it will be for the Europa League, where the UEFA payments will double in the event of like-for-like performances. (In order to give equivalence in proportional payout I have omitted West Ham United from the 2015-16 calculation, as only three clubs appeared in the Europa League in 2013-14.)

However, these 100%-plus increases in Europa League revenue do not tell the full story of the new Champions League paradigm. The maximum possible payout from the elite competition for an English club, which assumes that the Premier League champions win every group game en route to lifting the European Cup, while all their compatriot clubs go out at the group stage, would likely be around €92m (£62m, $100m). The minimum possible payment to an English club – having finished fourth in the Premier League and losing every Champions League game, would probably be about €25m (£17.5m, $27m).

So the base rewards this season will not be much less than Arsenal received for being group runners-up and a second-round exit under the previous cycle. Moreover, the top potential rewards from a 13-game Champions League are equivalent to two-thirds of the value of winning the title in a full 38-game Premier League season.

Comparing these maximum-minimum data side by side, here are what the relative UEFA payments could look like:

What is potentially now available to an English winner of the Champions League is a tremendous amount of cash. Fears that this money might distort the domestic competition have rightly prompted Premier League executives to make clear they will not move fixtures around to make Champions League entrants’ lives easier.

For the English top four, the minimum Champions League revenues from 2015-16 will again quite comfortably exceed the maximum available for the Europa League. Thus the incentive for European success this season has grown for Premier League clubs. And with it, so have the stakes for success and failure in the Premier League. Hence the increasing sums being spent by United, Liverpool and City in the transfer market this summer (with Arsenal and Chelsea presumably still to make their biggest moves).

For those clubs, and their investors like Henry and the Glazers, it is about protecting an investment that few others could afford. They are not in this game for the glory of it, but the money it continues to give them. For them, it’s a gas.

Related article: http://www.insideworldfootball.com/matt-scott/15946-matt-scott-don-t-bother-pitching-for-sponsors-if-you-re-not-winning-on-the-pitch

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is now a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him at moc.l1745236483labto1745236483ofdlr1745236483owedi1745236483sni@t1745236483tocs.1745236483ttam1745236483.