“The money coming into the game [football] is incredible. But it is just the prune-juice effect — it comes in and goes out straight away. Agents run the game.” Lord Sugar

Lord Sugar (then just plain Alan) became chairman of Tottenham Hotspur in 1991 and stayed at the helm there for 10 years. He was even manufacturer of the set-top decoder boxes that took content from dominant UK pay-TV channel, Sky, into British homes. He is truly a founding father of the modern English game.

But for the younger and more casual football fans whose acquaintance with Sugar principally as the face of UK version of The Apprentice, his best-known contribution to the game is his scatological quote on the finances of football. The reason is that – if you’ll pardon the pun – it really got to the pith of the business of English football.

Way back in February 2001, The Economist journal took Sugar’s ball and ran with it in a leader article on the national game. It noted he was “quitting as chairman of Tottenham in disgust” and saying of the so-called “prune juice effect”: “Any club which is not seen by its supporters to be spending every available penny on moving up the ranks risks obloquy; and with a limited pool of decent players, everyone is on a spending treadmill. Revenues go disproportionately to the winners, but in the effort to win, everyone’s costs rise to, and often beyond, the winners’ levels.

“Soon, something is going to have to change, for it looks as though football’s income from television may be nearing its peak. The broadcasters believe that coverage of football is approaching saturation point. New contracts will not provide the game with the huge increases every few years it has recently grown used to, and sponsorship too may wane. European clubs are going to have get a grip on their costs.”

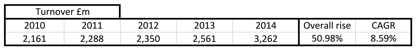

Yet over the past five years of available financial data, spanning three different TV cycles (2007-10, 2010-13 and 2013-16), the only change there has been is for there to be more growth – and across the piece in Premier League clubs’ activities. Matchday revenue is up 37.4% over the period (a compound annual growth rate of 6.6%), broadcast and media revenue has doubled, up 102.0% (CAGR: 15.1%), and commercial activity has risen still more quickly at 142.7% overall (CAGR: 19.4%). It all adds up to an overall picture that’s very healthy, as depicted in the table below.

This is not news to frequent readers of this column. Indeed, if anything, the only surprise would be the relatively modest growth in overall turnover during the five-year period. This can be accounted for by the slow growth in matchday revenues, which was once the league’s largest revenue segment. But that cannot detract from the fact that the Premier League story, as has often been recorded here, is one of tremendous financial success.

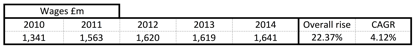

Now if history is to be any precedent, then surely the largest single element of the clubs’ cost base must be rising exponentially too. Yet the figures just do not bear this out.

It turns out that the rise in the wage expense payable to playing, coaching and office staff has been extremely modest. This is despite the onset of a new television cycle, a fact that completely bucks the trend. When the 2007-10 Premier League TV cycle elapsed and the calendar clicked into 2010-13, broadcast incomes rose a mere 4.5%. But at the same time players (mostly) and staff wrung 16.6% more out of their employers.

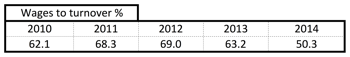

This time that has not happened. With clubs like Aston Villa and Manchester City trimming their wage bills and frugal newcomers like Crystal Palace replacing a Queens Park Rangers team that bust all its budgets, the overall expense rose only by a minuscule 1.4%. It put the all-important wages-to-turnover metric on a very even keel, as the table below shows.

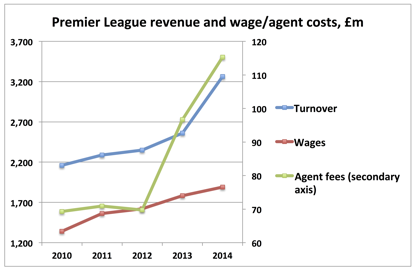

So is Sugar’s assessment no longer fit for purpose? Well, no. He certainly got one thing right all those years ago: agents are central to the commerce of the transfer market, and their importance is growing 15 years after he made his commentary. It is no coincidence that they have begun to do far better proportionately out of the new TV arrangements than their clients.

Now it is strongly possible that, with new TV contracts hugely raising the revenues of Premier League clubs from next season, that salary costs will already have leapt during this summer’s record transfer activity. But even so, it is unlikely to have outstripped the expected growth in club turnovers. Where there is likelier to be another big rise though is in what transfer intermediaries receive.

In the two most recently documented years, payments to agents have risen by more than 65%, a period in which club wage bills rose by only 1.4%. Perhaps this is a consequence of Financial Fair Play. It would be sound financial husbandry for Premier League clubs to offer inducements to the gatekeepers of player wages, the agents, in an effort to keep a lid on damaging inflation in what is by far the largest single element of a club’s expenditure. The morality of that, since agents generally work to player clients, would of course be in question. Indeed I have no evidence at all for that being the reason why some clubs have paid so much more to agents in recent times, but it is a thought.

Another reason for recent parsimony in the Premier League towards its players is to do with how clubs have tried to fix their own finances first and foremost. As discussed here last week [see related article below], clubs like Everton have made a good fist of that. But one further reason could be that some clubs are taking longer to renegotiate player contracts than previously.

The England forward Theo Walcott was allowed to enter the final year of his contract before a new one was signed, as have Mikel Arteta, Mathieu Flamini, Tomas Rosicky and Joel Campbell now. John Terry and Branislav Ivanovic, two key players for Chelsea over the years, are similarly in their last 12 months (and not exactly putting in performances deserving of renewals). This is also the case for Michael Carrick and, crucially, David de Gea at Manchester United.

Have economic considerations been behind the most notorious transfer story of the summer? There is talk of a “lucrative new contract” being offered to the Spain international goalkeeper De Gea, but many fans will be asking why United have left it so long. He has been on the same reported £60,000-a-week contract since his £17.5 million arrival at Old Trafford four years ago.

But that is not for want of United’s trying. For two years the club have been briefing media about his being on the brink of signing contract extensions raising his wages to £75,000 or £90,000 a week. Could this be coquettish flirting from De Gea’s agent, Jorge Mendes, in an ultimately unrequited courtship?

It is certainly possible. After the bungled contract exchange on the Spanish transfer-deadline day United will lose an asset widely regarded as one of the best goalkeepers in the world, worth perhaps £25-30 million in an open auction, for nothing. This will benefit not only Real Madrid, his still-likely destination but also the player and his agent. He will not be negotiating terms of £75,000 a week but perhaps double that amount.

As a very successful agent suggested speculatively to me on Tuesday, Mendes could stand personally to earn perhaps £15 million from the collapsed transfer the day before. In the same way that clubs would sensibly want agents to limit what players take, Real Madrid will want to guarantee Mendes delivers them their man after all the rigmarole of transfer-deadline day.

Because, prune juice or no, agents do indeed run the game.

Related article: http://www.insideworldfootball.com/matt-scott/17728-matt-scott-nothing-but-the-best-will-do-but-can-everton-really-do-better

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is now a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him at oc.ll1743665180abtoo1743665180fdlro1743665180wedis1743665180ni@tt1743665180ocs.t1743665180tam1743665180m.